TRANSCRIPT

INTRODUCTION

If you walk through

a forest anywhere in North America, you're likely to hear the scolding chatter

of a tree Squirrel. These lively creatures are among our most popular and

visible wild animals.

We watch Squirrels, in city parks or in our

backyards, collecting nuts and acorns to store for the Winter. But how much do

we really know about their life in the wild?

From the tiny Red Squirrel

to the handsome husky Fox Squirrel, these tree-top acrobats come in a wide range

of sizes and colors. Let's take a look at the unusual and often unseen behavior

of these "BUSHYTAILS."

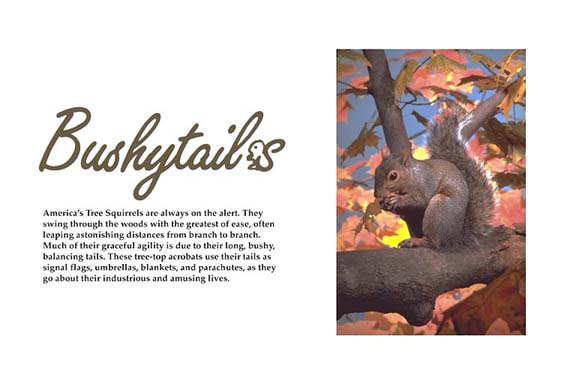

Squirrels are highly

specialized. They have adapted to the tree tops as have few other

mammals.

SQUIRREL RUNNING ON POWER LINE

With sharp, hook-like

claws for clinging to bark, and a large, fluffy tail for balance, they are

well-equipped for life above ground. One of the most notable characteristics of

Squirrels is their compatibility with humans. They arouse our sense of wonder

and they amuse us with their gravity-defying acrobatics.

Squirrels were not always as popular as they are today. During

colonial times, Gray Squirrels were so abundant that they threatened the crops

of pioneer farmers, especially their corn. It's been estimated that before the

dense eastern hardwoods were cleared for farmland, a billion Gray Squirrels

roamed the forests.

In the 1700's, bounties were imposed to control these

voracious pests. A few colonies even accepted Squirrel scalps as payment for

taxes. Colonists became such marksmen from shooting Squirrels, they devastated

the ranks of British soldiers during the American Revolution later.

Only

a small fraction of the once enormous Gray Squirrel population exists today. But

they are still the most familiar of all the North American

Squirrels.

DRAWING OF DIFFERENT SQUIRREL SPECIES Even more common

than the Gray Squirrel, yet rarely seen, is the nocturnal Flying Squirrel. This

species is our smallest native Squirrel, weighing only 2 to 3 ounces.

Even more common

than the Gray Squirrel, yet rarely seen, is the nocturnal Flying Squirrel. This

species is our smallest native Squirrel, weighing only 2 to 3 ounces.

The

Douglas Squirrel, below, also called Chicory, inhabits the coniferous forests of

our Pacific coastal states.

The Red Squirrel, above, makes up for its

small size by being the noisiest.

The versatile Gray Squirrel, so named

for its salt and pepper fur, is equally at home in woodland, suburb, or city

park.

The Ponderosa Pine forests of the western US. are home to the

beautiful Tassel-eared Squirrels, the Abert's Squirrel, on the right, and the

darker Kaibab Squirrel, on the left.

The Fox Squirrel is the largest of

all, weighing up to three pounds. This species exhibits a wide variety of color

phases.

The best season to

observe Squirrels is autumn, when most of their time is spent foraging on the

ground, collecting nuts and seeds. Like the Fox Squirrel, chipmunks also store

food for the winter.

Some of their favorites are Acorns, Hickory nuts,

Beechnuts, Walnuts and Maple seeds.

It was once believed that Squirrels

could remember where they buried each nut. But experiments indicate that, within

a half hour, they forget these locations. Now we know they find food, buried

under leaves and even snow by using their keen sense of smell. Ironically, the

nuts that Squirrels eventually dig up aren't necessarily the same ones they

buried.

With abundant food, the Squirrels fatten quickly. Their extra

weight will sustain them through the lean months ahead.

BURYING NUTS AND

SEEDS

Gray Squirrels are equally industrious. One ambitious bushytail can

bury thousands of nuts and seeds by the time winter arrives.

Each

Squirrel works fast and furious to hoard its winter food supply, for the

competition is intense. Deer, bears, hogs and turkeys also feast on the

nutritious mast.

GRAY SQUIRREL

Both Fox and Gray Squirrels are

found throughout the entire eastern half of the United States. They've also been

released into parts of the west. The adaptable Gray Squirrel has even been

introduced into England where it now drives out the native Red

Squirrels.

Both Fox and Gray Squirrels are

found throughout the entire eastern half of the United States. They've also been

released into parts of the west. The adaptable Gray Squirrel has even been

introduced into England where it now drives out the native Red

Squirrels.

Autumn is a time of restlessness for most animals, and the

tree Squirrels are no exception. Juveniles, born during February or March, must

leave their birthplaces and find a home of their own.

During this "fall

shuffle," the inexperienced young often fall prey to Hawks, Bobcats, Foxes and

Martens.

HUMAN HUNTER

Human hunters also stalk the colorful

woods.

Squirrels outwit their predators, human and otherwise, by hiding

behind a tree trunk until the danger passes.

HUNTER GATHERING SHOT

SQUIRRELS

Approximately 40 million Squirrels are shot annually by

hunters. While over-hunting can reduce populations in isolated woodlands,

Squirrel numbers are more influenced by severe weather and disease than by

hunting.

With the threat gone, the juveniles resume their playful

games.

All too soon, the fall colors slip

away.

RED SQUIRREL/WHITE FOOTED MOUSE

Only the high-pitched bark

of a Red Squirrel pierces the hush of the winter woods.

In cold weather,

Squirrels are rarely seen in the open. Even so, they don't hibernate like their

ground Squirrel cousins. The Red Squirrel of our northern Evergreen forests

avoids the icy winds by digging a network of tunnels under the

snow.

White-footed mice also seek shelter in the Squirrel's

tunnels.

The Red Squirrel is the most territorial of all the tree

Squirrels, with good reason. It caches nuts and pine cones in one pile which

must then be protected from other hungry

rodents.

COURTING/MATING

In late December, the mating season is

ushered in by a chorus of chattering Squirrels.

Squirrel courtship

involves more fighting than courting. Male Squirrels will chase a female for

hours in a frenzied attempt to mate with her. Though unwilling to mate at first,

the female leaves scent marks along the branches, enticing her suitors to

follow. Several males join in the chase and fight one another for mating

privileges.

It's believed that the female's protests serve to intensify

the competition between males.

The stronger the competition, the better

her chances are that the strongest, most dominant male will

persevere.

ALBINO GRAY SQUIRREL

An albino Gray Squirrel watches

the commotion from a nearby tree.

Besides eliminating the weaker or

inexperienced males as potential mates, the ritualized mating chases also

stimulate ovulation in the female.

The males are polygamous, meaning they

will mate with as many females as they can catch.

The interbreeding

between normal Grays and Albino's may produce offspring that are gray, white, or

even pure black. These color variations are simply genetic mutations in their

pigment and apparently have no bearing in matters of courtship.

FOX

SQUIRREL

While the Gray Squirrels range from white to black, Fox

Squirrels exhibit an even greater diversity of fur color, the greatest, in fact,

of any North American mammal.

For now, this male gives up the chase and

settles for a sweet taste of tree sap.

Squirrels are members of the

largest order of mammals, the Rodents. Fossil evidence suggests that rodents

originated in North America and evolved into many different species from a

common, Squirrel-like ancestor.

Rodents proved so adaptable that they

invaded almost every major ecological niche in an amazingly brief span of about

two million years.

The

appearance of springtime flowers, mushrooms and tree buds provides a banquet for

woodland creatures.

This female Fox Squirrel returns to her den to nurse

her four week old young, snuggled beneath a blanket of leaves.

A male Fox

Squirrel, with no parental responsibilities, continues to dine on the succulent

buds.

While male and juvenile Squirrels are very social and often den

together, neither are tolerated in the same nest as a female with

young.

FLYING SQUIRRELS/FULL MOON

Tree Squirrels are most active

at dusk and dawn, with one exception. As the moon rises, Flying Squirrels begin

their nighttime forays, gliding from tree to tree like furry kites. The Flying

Squirrel's name is a misnomer since it can't fly. But it can glide up to fifty

feet by spreading the loose flaps of skin along its sides.

Like most

Squirrels, they nest in natural tree cavities or abandoned woodpecker holes.

When fleas and other parasites become intolerable, the female moves her litter

to a new den. A baby finds comfort in its fresh bed of shredded

bark.

Tree Squirrels normally produce one litter a year, but, if food is

plentiful, they will nest twice. Once in early spring and again in mid- summer,

after the young from the first litter leave the nest.

MOTHER FLYING

SQUIRREL MOVING BABIES/NURSING

A typical litter for Flying Squirrels is

three, but there may be anywhere from two to six young. The baby Squirrels are

weaned at eight to nine weeks, but they may remain with their mother for up to

three months. Young tree Squirrels take longer to develop than most other

mammals their size. This ensures that their coordination and eyesight are highly

developed by the time they face life on their own.

About 10,000 years ago, a species of Tassel-eared Squirrel

inhabited the forests of the American southwest. As the Kaibab Plateau rose on

the north rim of the Grand Canyon, the Squirrels there became geographically

isolated from those on the south rim.

Two sub-species eventually

evolved.

ABERT'S SQUIRREL

The more common and widespread of the

Tassel-eared Squirrels is the Abert's Squirrel. Its range overlaps that of the

Ponderosa Pine, on which it depends for food and cover.

Besides eating

the pine cone seeds, the Squirrels survive the critical months of winter eating

the cambium, or inner bark, the Ponderosa.

They also eat Truffles, a

subterranean fungi. Truffles enhance the health of the forest by providing

moisture and nutrients to the pine tree's roots. The Squirrels help spread the

fungi by leaving spores in their droppings.

It's a three-way relationship

that helps to propagate the fungi and the pine trees, while providing food for

the Squirrels.

Living at an elevation of six to nine thousand feet their

mating season begins as late as April or May. The young are born about forty

days later.

KAIBAB SQUIRREL A subspecies of the Abert's, the

Kaibab Squirrel, was cut off from its ancestral population by the Grand Canyon

to the south and treeless deserts to the east, north and west.

A subspecies of the Abert's, the

Kaibab Squirrel, was cut off from its ancestral population by the Grand Canyon

to the south and treeless deserts to the east, north and west.

Separated,

they evolved distinctive characteristics such as a dark gray belly and pure

white tail. But the Kaibab, too, depends on the Ponderosa pine.

As with

other members of its family, mating is preceded by a high-speed chase through

the forest.

The Kaibab Squirrel provides scientists with a rare look at

how geographic isolation affects an animal's development. The few miles that

separate the Kaibab and Abert's Squirrels can be measured in thousands of years

of evolution.

We tend to give more attention to rare or seldom-seen

animals. Yet, however common, Squirrels are no less important.

We should

value tree Squirrels not only for their unique role in nature, but also for the

touch of wildness they bring to our civilized

world.

CONCLUSION

Squirrels provide us with a close-up look at

nature. We enjoy watching their antics and we benefit from them in another, less

obvious way. Since every buried seed or nut is a potential tree, the health of

our woodlands is enhanced by these rodents.

As long as their habitat is

preserved, forests will always resound with a persistent chatter of

"BUSHYTAILS".