One of the first impressions that someone introduced to taxonomy gets is that there is an inordinate fuss is made over the use of scientific names. Why not just use common names? They are easier to pronounce and remember than scientific names. However, scientific names have several major advantages over common names and it should become apparent that common names, at best, will never be more than an unnecessary accessory to the framework provided by the formal system of naming organisms (nomenclature).

There are several minor advantages to common names. They are simple and hence easy to remember, usually descriptive of the plant, and larger numbers of people will sometimes know what you are talking about when common names are used than is the case with scientific names. However, the problems with common names far outweigh any advantages. Some of the most obvious problems with common names are: (1). there are over 250,000 species of vascular plants and only a small percentage have common names; (2) the same name is often used for different plants; (3) common names are always in the local language, which prevents communication of plant identities between users of different languages; (4) there is no formal process for the application of common names, it is usually not possible to determine when a common name was first used and the identity of the plant or plants to which it was applied; (5) the same plant may have different common names in different regions. The formal system of nomenclature or "scientific names" deals with these and other problems very effectively.

The use of common names for plants can prevent the communication of information about plants because either a) there is no name associated with the plant in question or b) confusion about the plant's identity is almost guaranteed in communications between individuals in different regions of the country and world. The ability to communicate has probably been responsible for the development of human societies and cultures more than any other factor. In modern societies, the accurate communication of information has become critical to the ability of those societies to function. The advancement of our knowledge of plants is no less dependent upon the communication of accurate information. We may gather much useful information about a particular plant but if we cannot communicate the identity of the plant, all other information is useless.

NOMENCLATURE

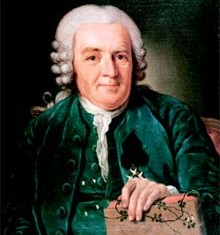

The system currently used in applying names to plants, known as nomenclature, had its beginning with Carolus Linneaus. Species names have three components: (1) the genus name; (2) the specific epithet; and (3) the authority or individual(s) responsible for the name. Components 1 and 2 are either italicized or underlined. An example is Quercus alba L. Quercus is the genus name for the group of plants commonly known as oaks. The specific epithet is alba, Latin for white, and is descriptive of the bark and wood of the plant commonly known as white oak. The authority is L., an abbreviation for Linneaus, who first coined a formal name for this plant.

The system currently used in applying names to plants, known as nomenclature, had its beginning with Carolus Linneaus. Species names have three components: (1) the genus name; (2) the specific epithet; and (3) the authority or individual(s) responsible for the name. Components 1 and 2 are either italicized or underlined. An example is Quercus alba L. Quercus is the genus name for the group of plants commonly known as oaks. The specific epithet is alba, Latin for white, and is descriptive of the bark and wood of the plant commonly known as white oak. The authority is L., an abbreviation for Linneaus, who first coined a formal name for this plant.Since the time of Linnaeus, the system of nomenclature has become more formalized and codified. The International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN) has been established to provide a uniform set of rules to be followed in applying names to plants. The rules contained in the ICBN are revised during the International Botanical Congresses, which are held every six years. The core of the ICBN is composed of six principles:

1. "Botanical nomenclature is independent of zoological nomenclature." The rules of the ICBN do not apply to animals and bacteria. Therefore botanists do not have to be concerned with the names or rules associated with animals and bacteria.

2. "The application of names of taxonomic groups is determined by means of nomenclatural types." Each plant has a physical (type) specimen associated with it. A plant taxonomist doing research has to study type specimens in order to ensure that names associated with plants are correct. The most important specimen is the holotype. The holotype designated by the researcher is the specimen to which a name is permanently attached. There can be only one holotype. Isotypes are duplicates of the holotypes, i.e., specimens collected by the same person at the same time and location as the holotype. The holotype is deposited in a herbarium of the author's chosing and isotypes are usually distributed to major botanical institutions, such as the New York Botanical Garden, Missouri Botanical Garden, and the Smithsonian Institution. This insures that there will be additional specimens available in case the holotype is lost or destroyed. Unfortunately, the rules that require the designation of holotypes and isotypes for species descriptions are relatively recent. Therefore, there are many names that do not have holotypes or isotypes associated with them. When a holotype is not available, either due to its lack of designation or its destruction, other kinds of types must be designated. Syntypes are specimens cited by the author when a holotype was not designated or has been lost. A lectotype is a specimen designated by a later investigator when no holotype is available. It is selected from the isotypes or syntypes. If all the material that can be identified as being studied by the original author (holotypes, isotypes, syntypes) has been destroyed, a neotype is designated as the nomenclatural type.

3. "The nomenclature of a taxonomic group is based upon the priority of publication." The rule of priority means that the earliest applicable, properly published name is the correct one. Priority extends back to 1 May 1753 for most plants, the publication date for Linaeus' Species Plantarum.

4. "Each taxonomic group with a particular circumscription, position, and rank can bear only one correct name, the earliest that is in accordance with the rules, except in specified cases." The names that can be considered as the correct names are those that are published effectively and validly. Effective publications requires "distribution of printed matter (through sale, exchange, or gift) to the general public or at least to botanical institutions with libraries accessible to botanists generally." Valid publication requires effective publication of a name in the form specified by the ICBN. A description and Latin diagnosis (short description) of the new taxon are required. It often occurs that there is more than one effectively and validly published name for a taxon. In that case, the oldest applicable name is the correct name and the other, more recent names are synonyms. If the same name has been used for two different taxa, the taxon first named is the one correctly associated with the name. The later use of the name is illegitimate and the name is referred to as a later homonym. All of the names associated with a particular taxon are usually included in formal treatments.

5. "Scientific names of taxonomic groups are treated as Latin regardless of their derivation." The ICBN provides instructions on the use of proper Latin grammar for taxonomic names.

6. "The rules of nomenclature are retroactive unless expressly limited." This means that the rules apply to work done before the acceptance of these rules.

How, then, does a Plant Taxonomist proceed in a revision or reinvestigation of a taxon? Let us assume that the investigation is being done at the genus level. The investigator must first decide which plants belong to that genus (circumscription). This may require the investigation of members of related genera. Once the genus has been circumscribed, the next step is to decide how many infrageneric taxa are required. This is generally done at the species level although some workers designate infraspecific taxa (subspecies and varieties). Let us assume that the only infrageneric level used is the species rank. Once species circumscriptions are done, the species descriptions can be prepared. All the type specimens associated with the genus must be studied in order to determine the correct name for each species. Then, descriptions, which include the designation of nomenclatural types and the listing of synonyms, are prepared and submitted for publication in a scientific journal.

Below is a list of names in an actual revision. The author has looked at the type specimens associated with these names and has decided that they all belong to the same species. All of the names were published validly and effectively.

The names are:

Hypericum hypericoides (L.) Crantz - 1766

Ascyrum hypericoides L. - 1753

A. crux-andreae v. angustifolium Nutt. -1818

A. linifolium Spach - 1836

A. oblongifolium Spach - 1836

A. montanum Raf. - 1838

A. plumieri Bertol - 1853

A. macrosepalum S. Brown - 1912

A. hypericoides L. v. typicum Fern. - 1936

A. hypericoides L. v. oblongifolium (Spach) Fern - 1936

You can tell something about the research history of a taxon by just looking at the names and dates associated with the names. Linneaus was the first to work on this taxon, placing it in the genus Ascyrum and naming it Ascyrum hypericoides L. This was done in 1753 and Ascyrum hypericoides L. is the oldest legitimate name for this taxon. Crantz decided that it belonged in the genus Hypericum and gave it the name Hypericum hypericoides (L.) Crantz. This particular name tells us that the specific epithet hypericoides was first used by Linneaus but that Crantz moved it from another genus to Hypericum. Other workers named a number of different species and varieties at later dates and placed all of them in the genus Ascyrum. The most recent worker who worked on this genus decided that this taxon belonged in the genus Hypericum and that all the types associated with all the other names were the same taxon as Hypericum hypericoides (L.) Crantz.

Now some questions.

1. What is the type specimen for Hypericum hypericoides (L.) Crantz?

2. The oldest legitimate name for this taxon is Ascyrum hypericoides L. but that name is not being used. Why?

3. The name of the taxonomist who most recently worked on this group and decided that Hypericum hypericoides (L.) Crantz is the correct name does not appear anywhere in any of the names. Why?

4. Are there separate type specimens associated with all the other names that are listed above?