Ben Harder

National Geographic News

May 3, 2002

|

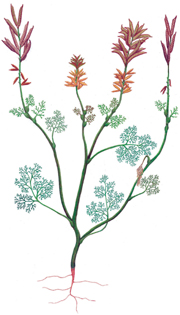

Based on the age of the rock in which they found it, the fossil's discoverers believe this plant, Archaefructaceae, lived at least 124.6 million years ago, during the dinosaur-dominated early Cretaceous period. That date makes it among the earliest of flowering plants. Photograph courtesy Science |

From a bed of volcanic ash deposited in northeastern China more than 124 million years ago, botanists have recovered impressively complete fossils of some of Earth's earliest flowering plants.

The discovery of this new family of plants sheds light on the life and times of early members of an enormous category of flora, which includes flowers, trees, and many life-sustaining crops.

"Flowering plants are the dominant vegetation in the world today," says David Dilcher of the University of Florida in Gainesville, who is one of the new fossil's co-discoverers. "They're the basic food crop and fiber source for the world's population."

Dilcher and his five colleagues, including four Chinese researchers, found the fossil in a sand-colored slab of stone that they extracted from a fossil-rich rock formation northeast of Beijing. They dubbed the fossil species Archaefructus liaoningensis and Archaefructus sinensis. Together, the finds make up the family Archaefructaceae.

"When we study [Archaefructaceae], we're looking at the ancestry of what sustains us in the world today," says Dilcher. "It's useful for us to understand the relationships among flowering plants, especially in this day of molecular genetic manipulations."

The finding could also help scientists understand the evolutionary history of the flowering plants—where they began and how they gave rise to so many modern species.

Flowers in Water

Based on the age of the rock in which they found it, the fossil's discoverers believe the plant lived at least 124.6 million years ago, during the dinosaur-dominated early Cretaceous period.

That age makes Archaefructaceae among the earliest of flowering plants. Pollen grains of even more ancient flowering plants, dated to about 130 million years ago, represent the oldest known evidence of flowering plants.

Similarly aged fossils have been found of waterlilies, another type of flowering plant that persists today and, like Archaefructaceae, lived in the water.

The same fossil bed yielded evidence of similar flowering plants several years ago, but the fossil traces of the organism were much less complete, and Dilcher and his colleagues were forced to guess about certain characteristics.

"These are the earliest, most complete remains of flowering plants yet discovered," Dilcher says. "What's spectacular about these fossils is that all parts of the plant are present, including the roots, leaves, and reproductive organs."

The nearly intact specimen enabled the researchers to determine that it grew in watery environments. It wouldn't have been able to support its own weight on land.

The feather pattern of its leaves also indicates that the plant lived in the water, Dilcher says, an observation that is further supported by the fossils of fish found in the same slab. It probably lived in a shallow lake populated by dinosaurs, crocodiles, turtles, and numerous types of fish.

Archaefructaceae's seeds are enclosed inside fruits, a characteristic that separates flowering plants from more primitive seed-producing plants.

Interestingly, however, petals—typical of many flowering plants—are absent. Given the quality of the fossil's preservation, they were not apparently lost during the process of fossilization. Instead, it seems, this plant never had petals.

"It's a really incredible fossil," says Michael J. Donoghue of Yale University. "It's spectacular that they've got a specimen that shows pretty much the entire plant," he says.

First Flowers?

The researchers analyzed the fossil to determine where it fits into the evolutionary tree of the plants. By comparing the physical forms of related ancient and modern organisms, scientists can make educated guesses about which are most closely related and in what order various innovative features evolved.

Based on their analysis, Dilcher and his colleagues conclude in the May 3rd issue of the journal Science, Archaefructaceae was a sister family to all living flowering plants.

That means that Archaefructaceae diverged from the flowering plants before the ancestor of all modern members of the group arose, making it as close to the original flowering plant as any fossil yet found.

That raises the possibility, says Dilcher, that flowering plants actually evolved in aquatic environments, a scenario that runs counter to conventional wisdom.

Other scientists, however, say it's difficult to evaluate exactly where the new fossil fits in among flowers. Several suggest that the fossil may have been an early, petalless variation on the waterlily—another aquatic, flowering plant—that ultimately went extinct.

"It would be fascinating if there were several separate lineages [of early flowering plants] that were exploring life in the water," says Donoghue. But from the limited data the researchers presented in the paper, he says, "it's not clear to me why they reached this conclusion."

Even if there were two lineages of early flowering plants that were aquatic, says James A. Doyle of the University of California, Davis, "it would still be a pretty wild hypothesis to say flowers evolved in the water."