|

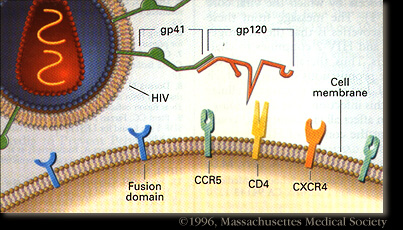

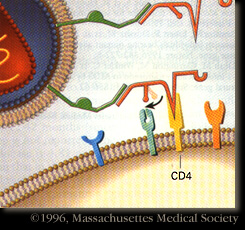

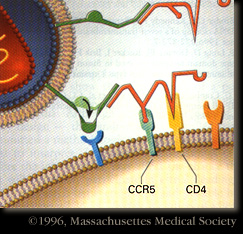

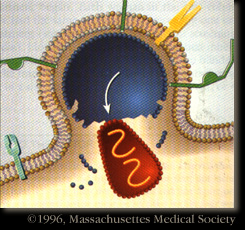

Interaction with Host Cell: When the virion approaches the macrophage, the interaction between the virion's gp120 with the CD4 receptor on the surface of the macrophage, causes gp41 to extend. Conformational changes in the structure of both the viral envelope and the CD4 receptor permit the binding of gp120 to another cell-surface receptor, such as the chemokine receptor CCR5.

|  |

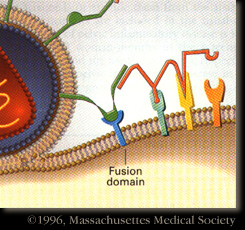

Cell Fusion: This second attachment brings the viral envelope closer to the cell surface, allowing interaction between gp41 on the viral envelope and a fusion domain on the cell surface. HIV then fuses with the cell. Subsequently, the viral nucleoid enters into the cell, most likely by means of other cellular events. Once this stage is achieved, the cycle of viral replication begins.

|  |

CCR5 Mutation: Some people, primarily of northern European descent, have complete immunity from AIDS in spite of exposure to HIV. They are homozygous for a mutation that changes the structure of the CCR5 chemokine receptor. The result is that the virion cannot attach to the cell, which prevents fusion. Scientists initially thought that the mutation, already in the population during the Middle Ages, was favored because it conferred resistance to the bubonic plague. But it could have an advantage against smallpox or some other disease(s), in which the infectious agent uses essentially the same mechanism to enter the host cell.