Stanislaw Lem's Critique of Cybernetics

(University of Manitoba; Fall 1984): 53-71.

The worship of technique is, in fact becoming the dominant religious reality of our culture. --Frederick Ferre, Shaping the Future.

nau | english | rothfork | publications | Lem: Memoirs Found in a Bathtub

| Memoirs Found in a

Bathtub: Stanislaw Lem's Critique of Cybernetics |

|

| An earlier version of this

essay was published in Mosaic 17.4 (University of Manitoba; Fall 1984): 53-71. |

|

The worship of technique is, in fact becoming the dominant religious reality of our culture. --Frederick Ferre, Shaping the Future. |

![]()

Had Rene Descartes written fiction, it might have resembled that of Stanislaw Lem. For Descartes first called attention to the possibility of separating the activity or process of consciousness from its products. Lem's work largely illustrates this epistemological concern, demonstrating how we acquire a paradigmatic vision or gestalt within which we construct "truth"; we seek, Lem observes in Memoirs Found in a Bathtub (1973), "the Cause of the Effect, the Effect that in turn causes Action, and so a continuity is established" becoming -- as David Hume might have also said -- "the chains that bind us" (Memoirs 29). Descartes' "epistemological turn" in philosophy is familiar to twentieth century Westerners as the "linguistic turn." Postmodernism has familiarized us with how language creates meaning. It has also further sensitized us to Kant's distinction between noumenon (the thing in-itself) and phenomena (the thing as we perceive and/or conceptualize it). Thus Richard Rorty says: "We need to make a distinction between the claim that the world is out there and the claim that truth is out there." He reminds us that "where there are no sentences there is no truth." Hence, "Truth cannot be out there -- cannot exist independently of the human mind -- because sentences cannot so exist, or be out there. The world is out there, but descriptions of the world are not" (4-5).

Postmodern epistemology is not solely produced by language analysis. Much of the postmodern view can also be produced from developments in the philosophy of science. For example, Werner Heisenberg made nearly the same point as Rorty when he said: "This again emphasizes a subjective element in the description of atomic events, since the measuring device has been constructed by the observer, and we have to remember that what we observe is not nature in itself but nature exposed to our method of questioning. Our scientific work in physics consists in asking questions about nature in the language that we possess" (58). Thomas Kuhn's immensely influential The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) suggested a postmodern epistemology by studying the history of science. This is significant because Stanislaw Lem is a postmodern writer whose East European influences came from the philosophy of science, and from sources in the philosophy of language that are not very familiar to Western scholars. This has caused him to be both ghettoized and ignored as a science fiction writer and, paradoxically, to have a reputation as more enigmatic and esoteric than Jorge Luis Borges, Vladimir Nabokov, or Michel Foucault.

There are six million copies of Lem's novels, short stories and plays in print throughout East Europe and the Soviet Union. Over two dozen of his works have been translated into English. Among the best known are Solaris (1970; the Soviets made a major film from this novel), The Cyberiad (1974; perhaps his best work), The Futurological Congress (1974), and The Star Diaries (1976). Trained to be a physician, and "brought up with the scientific outlook" by his father who was also a physician, he subsequently "spent many hours over coffee arguing about God" with his friend Karol Wojtlya who taught theology in Krackow and who is now better known as Pope John-Paul II. In an interview, Lem indicated his thinking on religion: "for moral reasons I am an atheist -- for moral reasons. I am of the opinion that you would recognize a creator by his creation, and the world appears to me to be put together in such a painful way that I prefer to believe that it was not created by anyone than to think that somebody created this intentionally" (L. W. Michaelson, "A Conversation with Stanislaw Lem: Amazing (Jan. 1981): 116-19. Peter Engel, "An Interview With Stanislaw Lem: The Missouri Review, 7, 2 (1984): 218-37. Also see Raymond Federman, "An Interview with Stanislaw Lem," Science-Fiction Studies, 10 (1983): 2-14).

In the broadest view, Lem's work explores the nature of consciousness/language and how it constructs relational fields or gestalts to produce "truths." More specifically, like Thomas Kuhn -- who speaks for a tradition going back to David Hume and Rene Descartes -- Lem explains that science is a game that constructs models to reveal relationships that would otherwise be unrecognized. Sensitive to both the epistemic limits of science and the power of technology, Lem feels that "Directly, man will probably never be able to understand and recognize everything, but in an indirect manner he will be able to get a command of everything." Thus in science today, "we are talking about things which are no longer within the grasp of our senses. The scientist's mathematical apparatus is like a cane in the hand of a blind man. He doesn't see the world directly, but by hitting the ground with his cane he can hear the echo and can recognize whether he is coming close to an obstacle. But you cannot really say that the blind man is thus able to see a wall. And by this circuitous route we continue to manipulate things. In other words, all knowledge is subjective" (Engel 235-36). However, this game can also become an end in itself, a technique obscuring instead of illuminating the reality it seeks. Thus David Lovekin warns: "As technical consciousness develops and as the body and other natural objects retreat to the perceptual and conceptual horizon, the object of technical consciousness becomes technical consciousness itself" (203-21).

In Memoirs Found in a Bathtub, Lem extrapolates affects of a cybernetic psychology to demonstrate how the arbitrary models it might build could proliferate, both in number and complexity, finally to subvert the process of discovering depth and meaning in our embodied experience through involvement in archetypal patterns and rituals. This indicates why critics like Leslie Fiedler feel that "Lem fears language, which, controlled by bureaucrats and theologians, can distort our perception of the world" (Quest 79-82). Language and cybernetics refer to technique and interpretation (the operations of consciousness), not to primal, embodied experience (sensations). The fundamental clash, revealed in Memoirs, is between the paradigm of cybernetic psychology and that of depth psychologies. Consequently, cybernetics must be driven to confront philosophically the depth of human situations, to recognize what Michael Polanyi calls, "the tacit dimension," if it is to be anything more than another expedient technique: for "technique cannot produce the philosophy that directs it" (Knowing and Being 105). It "knows" only the linear sequence of steps that define it. It does not have the depth or philosophic vision that comes with being outside the set and considering the set, or technique, as a whole. In Memoirs, Lem illustrates the inadequacy, and the meaning-destroying affect, of artificial technique, which increasingly regulates contemporary life.

Now it is true that in his nonfiction, such as his Summa Technologiae (untranslated in English), Lem seeks to define cybernetics and technology as morally neutral epistemological structures. Pragmatists would object that this is an empty claim. But this should not prevent us from allowing Memoirs to make its own dramatic statement on technique. And this is especially important in light of Lem's semiotic theory of literature. For, as Jerzy Jarzebski explains: "Lem considers the processes of literary communication as play, and yet establishing the socially recognized meaning of a work is a process of stabilizing meanings within changing cultures. He relies upon the apparatus of the information theory, probability theory, and the theory of games . . . . [He treats] the meaning of a literary work as the result of stochastic processes" (126). Truly stochastic processes cannot have meaning in the way that human embodied experience has meaning and emotional depth. Someone else may interpret my experience as random or the result of chance events, but no one experiences her life that way. Husserl tells us that consciousness is intentional. It generates meaning.

"Cybernetics," a term derived from the Greek word for "steersman," denotes a system of goal-oriented actions modified by feedback to determine the difference between a present state and a specified ideal state or goal. The essential characteristic of a cybernetic system is the lack of predetermined specific technique or means to reach a goal. It is radically utilitarian in being able to use trial and error to test, any and all, available alternatives to reach a goal. Thus, the feedback loop allows change and creates the semblance of decision and choice. If an observer is not cautious to recognize the pathetic fallacy of how she attributes her own intentions and motives to the system, especially if it is a complex system such as those of computer science, it is easy to imagine that there is a "tacit dimension" -- an intelligence or consciousness -- at work behind the activities, independent of the observer. Memoirs is a dramatic illustration of this fallacy. The narrator of the Memoirs finds himself in situations defined by relations that are arbitrary choices in a cybernetic system. Consequently, his attempts to fathom the meaning of sequences or symbols is futile: his simulated experience is a nightmare which cannot be interpreted.

In contrast to the temporary and entirely pragmatic steps in a cybernetic system, myth, which originates in dreams and the unconscious -- from what Michael Polanyi calls, "the spontaneous organization of mind" -- reifies methodical experience into rituals, archetypes and social patterns, which eclipse the pragmatic ends they serve (Faith and Society 38). For example, in India, Hinduism is called the "eternal law" (sanatana dharma), which, as in The Lawbook of Manu, specifies situations and appropriate action, depending on the time of life, social relations (caste), and stage of development or level of understanding of the actor. Most people are absorbed in the technique (karma marga) specified by the myths and archetypes that provide meaning to their lives. About such structures, Joseph Campbell writes: "The highest concern of all of the mythologies . . . has ever been that of suppressing the manifestations of individualism; and this has been generally achieved by compelling or persuading people to identify themselves not with their own interests, intuitions, or modes of experience, but with archetypes of behavior and systems of sentiment developed and maintained in the public domain" (The Flight of the Wild Gander 163). In a sense, then, people who accept myths literally and expend psychic effort in fantasied dialogues with mythic characters in a system of mythic patterns, remain asleep, living in a dream which pervades the more pragmatic or personally experienced world. Campbell concurs, saying: ""Since the ultimate reference of religion is ineffable, many of those who live most sincerely by its mythologies are the most deceived" (Masks of God: Primitive Mythology 55). Enraptured in the steps of a timeless dance, those immersed in a mythic world view do not perceive life as a project or heurism to reach a goal. Their life is a dance or a drama, not a cybernetic network nor John Pilgrim's progress.

A scholar on Hinduism tells us succinctly that "The Indian thinks [in order] to appreciate; the Westerner thinks [in order] to possess" (Organ 315). Like Isaac Newton, the Westerner wants to possess the game-plan for the universe. He wants to conceptually understand in order to technologically control. This attitutde has a Greek foundation in logos: "The quest for reality assumes that reality can be known" (Organ 40). There are three positions at issue. Na´ve science assumes that reality can be known; the logos "out there" is believed to be mirrored in language/math. Lem's fiction breaks the mirror or at demonstrates how the mirror can distort images. Western depth psychologies, pragmatism, and Asian outlooks deny the premise that reality can be known as an object. They insist that all knowledge arises subjectively. Nonetheless, there is a recognition in the Indian tradition that it is futile to continue responding or playing prescribed roles in mythic systems, because these are endless. To escape these fundamentally disappointing roles, the dreamer must awaken, cease to respond unthinkingly, and begin to perceive an entire pattern. In this way he becomes free to choose which parts to play, how long to play them and, most importantly, he achieves an emotional distance from the (social) character he plays. Knowing that his acts are prescribed by a pattern or culture, the actor gains an aesthetic distance that enriches the drama by creating depth. Joseph Campbell puts this succinctly: "The constriction of consciousness, to which we owe the fact that we see not the source of the universal power but only the phenomenal forms reflected from that power, turns superconsciousness into unconsciousness and, at the same instant and by the same token, creates the world. Redemption consists in the return to superconsciousness and therewith the dissolution of the world" (Hero 259). The opposite of this is the obsessional personality, which feels threatened at the loss of control or possession. The danger is in obsessionally following technique so that its status as a means-to-an-end is lost sight of. Then the pattern becomes nightmare. Henry Adams had something like this contrast in mind when he wrote: "Chaos was the law of nature; Order was the dream of man" (451). Today, one of the dreamers, a theologian no less, writes that, "technique brings an end to the mythological conception of transcendence" (Vahanian 23). This statement could serve to introduce a pragmatist epistemology, but Vahanian has in mind a kind of Romantic Hegelianism in which the organic life-force follows the laws of set-theory to germinate visions from silicon chips. Correspondingly, Lem's narrator, wandering in an endless maze of corridors, cannot even conceive of a way out, a life transcending technique.

The nightmare described by Memoirs is the result of intersecting cybernetic systems. Ritual actions are abstracted from Christianity, capitalism and nationalistic militarism. They then become fused by short-circuiting to create a nexus or technique without meaning or goal, so that, "words now merely mean other words, symbols mean other symbols," and "the natural world, the world of nature," is "replaced by . . . the world of technique" (Lovekin 203, 206). A recognition that this paradigm is warped can be made only by someone standing outside the system, which is the perspective of readers. Because the author of the Memoirs is a product of cybernetic psychology, he has recourse only to the technique of his mono-dimensional world. He has no recourse to judgment arising from the tension between two or more communities. For example, when religious discourse threatens to become obsessional, our experience in the discourse communities of science and civil law offer counterbalances fostering a personal judgment that requires experience in all three communities. Instead, the narrator repeatedly attempts to find psychological depth and meaning in his artificial and broken world, even as many of us try to find meaning in a world fabricated by the technologies of Madison Avenue, Wall Street, Hollywood, the Pentagon, and Crystal Cathedral of Rev. Schuller.

Memoirs is prefaced by an apocryphal introduction written by a thirty-second-century historian attempting to reconstruct life inside the "Third Pentagon," the last insane refuge of the "American Ministry of Defense"; it is "a kind of collective military brain" (10) produced after "the Great Collapse" when all paper was destroyed. Lem does not articulate the steps of the "papyralysis" which destroys our world, but with this fictional incident he invites readers to consider a cybernetic history. In fact the Canadian historian, Harold Innis, proposed such a theory and found an articulate spokesman for it in Marshall McLuhan. Innis used Marx's historical paradigm, substituting cybernetics for economics as the fundamental causal mechanism. Thus, Innis suggested that information systems cause the social patterns that emerge in any era. Consequently, in a very literal sense, the means (technique) cause the end, as Marx said. For Innis, the key to any historical period is the communication system it used. For example, Innis suggests that cuneiform script, ziggurats and pyramids imposed a strong temporal-mythic ontology which fostered an identification with timeless, other-worldly values, whereas the Homeric oral tradition fused its technique of linear chronology with the alphabet and papyrus to create a spatially oriented paradigm evident in the roads of the Roman Empire. According to Innis, paper largely created the Renaissance, or at least the conditions necessary for the Renaissance, and led to the triumph of the spatial model and the consequent suppression of the oral tradition and its products: myth, epics, religion.

Marshall McLuhan turned from history to speculate on the future, suggesting that as we use more electronic media — especially television (including, I would add, the Internet as another TV channel) -- we will spend less time reading and writing and consequently will lose the bias toward linear or sequential thinking and begin to inhabit a "global village." (Lem alludes to McLuhan in other novels. For example, in The Chain of Chance he says, "McLuhan's prophecies were coming true," (119). McLuhan is said to have been a secret agent from the future in The Star Diaries, (185). Lem's "papyralysis" is a metaphor for this process. Using McLuhan's favorite metaphor, we might imagine each ego to be a television/computer monitor tuned to the program of society. The crucial question -- which may be already answered by the choice of the machine metaphor -- is, how is the program produced? Is it created by myth and archetypes originating in dreams, which in turn originate in the unconscious and hence in the embodied experience of life itself; or is it produced by a cybernetic system where the goal is everything and the process arbitrary? Myth, says Thomas Mann, "is the foundation of life . . . the pious formula into which life flows when it reproduces its traits out of the unconscious" (89). But in this age of "artificial intelligence," the unconscious is considered only a ghost in the machine or, perhaps, snow on a TV screen without a message.

Memoirs illustrates a world produced by cybernetic psychology; by the assumption that people are simply robots or as the prominent MIT computer scientist Marvin Minsky says, "meat machines." Lem accepts the cybernetic metaphysics -- as old as Leucippus and Democritus — that the world is assembled from atomic bits/bytes, and consequently rejects the tacit dimension of the creative unconscious or any less Romantic pragmatist epistemology. Several stories in Lem's Memoirs of a Space Traveler deal with such issues. In one, we are told of "the dream of cyberneticists — a self organizing substance." Materialism is further apparent in Lem's admission: "Actually, I am influenced primarily by various philosophers. Bertrand Russell, Wittgenstein -- the so-called ‘Viennese Circle'" (Memoirs of a Space Traveler 130). In Lem's cybernetically booted-up world, a space probe brings back a catalyst that instantly destroys paper. Thus all linear culture and thinking, based on reading and writing, are lost; people are "deprived of their identity," lose "their reason," and their technology: "the supply of goods broke down" (3). People revert to mythic, non-linear patterns, which, to be precise, should not be called "mythic" because they do not and cannot originate from dreams and the unconscious, since these are denied any reality. This pseudo-myth is the product of a cybernetic system, which, since it has lost the goal provided for it by the unconscious, can never end. And, because the endlessly repeated actions are arbitrary techniques and not organic patterns of growth, which culminate in transcendence, there is only the simulation of myth, just as there is only a simulation of language evident in computers.

The "papyralysis" destroys our world like a house of cards: "technology, research and development, schools -- all crumbled into nonexistence." In the new medieval "global village," knowledge is again "disseminated orally." The ecology of paradigmatic views, sustained by what Polanyi calls "self-determining communities: of scientists, scholars, lawyers, and judges, artists of all sorts, and churchmen," is lost (Meaning 198-216). There is no commitment to visions defined in these communities. Instead, there are simulations: inconsequential cybernetic "choices" of technique within a monolithic and reductive bureaucracy. "The human race knew next to nothing of its own past" (3-5). But in mythic, dreaming societies, such as ancient India, the past is the future; the present an eternal dream.

Though Lem fictionally destroys the modern world, he does not attempt to start human evolution over again. The cybernetic postmodern world is scavenged from pieces of the old world. However, we know from Thomas Kuhn's work that pieces taken from a precedent paradigm do not fit into alternative paradigms. For example, in the shift from Newton to Einstein, even the most basic definitions of time, space and causation changed. In the nightmare montage of Memoirs pieces from several of Polanyi's self-determining communities are fused into a cybernetic monolith, symbolized by the buried pyramid. (Campbell interprets the funeral cult of Egypt and its great pyramids as anti-mythic. For with the pyramids there is no longer "Mythic identification, ego absorbed and lost in God, but its opposite, mythic inflation, the god absorbed and lost in ego," Masks of God: Oriental Mythology 80.) Instead of a paradigm shift, in which the new paradigm subsumes the old, such as happened with Copernicus and Ptolemy, there is a medieval reductionism capitulating to one faith, cybernetics, which jumbles the structures cannibalized from other paradigms in endless and random technique. Thus Lem's historian explains that the "worship of the deity Kap-Eh-Taahl . . . became one of the dominant cults." The deity was also called "Almighty Da-Laahr" and had a religious order called stock brokers devoted to an appraisal of its fluctuations. Understanding the nature of this deity is difficult because "Kap-Eh-Taahl was denied any supernatural existence . . . he was, to all extents and purposes, equated with assets, liquid, fixed, and hidden, and had no existence beyond that" (7).

To be sure, this satire is aimed at Jeremy Bentham and Adam Smith, but it does not end there. If it did, Lem would likely propose a counter technique and a counter paradigm, such as Marxism or Christianity. He does not, because his deeper aim is to cause a shock of recognition by showing us how deeply we profess in technique, how we have almost no way to imagine that humans are anything other than meat-machines, and that the life of the mind is mere calculation. The opposite view is articulated in Hannah Arendt's criticism of the cybernetic faith and its icon, the computer: "there exists no metaphor that could plausibly illuminate this special activity of the mind, in which something invisible within us deals with the invisibles of the world" (Life of the Mind 123). Arendt implies Platonism, Stoicism or some other type of Western transcendentalism, which is so incommensurate with cybernetic materialism that it stops conversation. After saying he was mistaken in everything, Thomas Hobbes has nothing more to say to Plato; and vice-versa. However, the conversation continues, entertainingly, between cybernetic materialism (where the reductive metaphors are spatial) and Asian outlooks (where the metaphors never escape a temporal dimension).

In his interview with Engels, Lem talked about his plans for Golem XIV, a novel based on the idea of a supercomputer as "a creature which has no ‘I,' no ego." Although he does not call it karma, Lem does say that "Human intelligence or rationality is not free . . . because it is meant to operate the body in its struggle for survival . . . . Golem considers itself to be the first intelligent creature liberated from these bounds [ karma ]." Thus Golem, "in its own spiritual life . . . does not have any ego, any concrete personality." This is said to be the condition of a Hindu saint, a jivan-mukit (a life free from karma), or a Theravada Buddhist saint, an arhant (one in whom the flame of desire/tanha is extinguished). Such epistemological parallels with Asian thought remain largely vestigial in Lem's work. For his avowed allegiance is to materialism and cybernetics. Nonetheless, such parallels between East and West may be of crucial importance in reconciling contemporary science and traditional values. Nor should we be dissuaded from identifying such parallels by the intentional fallacy; nor by critical ignorance and ethnocentrism.

The major shrine in the world preceding that of Memoirs was a pyramid, an architectural computer, called the Pentagon, "where crusades were planned against the Heathen Dog" (8). A Second Pentagon was built, mostly underground, symbolizing a dislocation of reality through repression, a descent into the unconscious, which is not organic or alive, but cybernetic. References to a Third Pentagon were thought to be entirely mythic, the structure "raised purely in the minds and hearts of the faithful" (9). However, the Third Pentagon did exist in the NORAD military complex inside Cheyenne Mountain, Colorado. And it was to this pyramid/ark that the faithful went, when "the populace of Ammer-Ka went over to the side of the ‘heretics.'" In a surreal parody of American millennial and utopian fantasies, the Third Pentagon sealed itself from the profane world and "thrived exclusively on the myth, the legend of the glory that was Kap-Eh-Taahl" (11). This is no longer John Winthrop's "beacon on a hill" shining the good news of a perfected community to the rest of the world. It is the next step in a descent from Brigham Young's Zion walled from the profane world, imploding in paranoia and neurotically distorted myth.

Memoirs is a carnival-mirror image of Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress in which Mr. Christian runs through mazes that form elaborate circles. A personal confession, Memoirs seems something like an amalgam of Kafka and Kierkegaard. Human questions concerning meaning, identity and destiny are unanswerable because there is only "data" and not life. The narrator is a product of an artificial world where all relations are cybernetic "choices" made in pursuit of a lost military goal. Military discipline is maintained in order to retaliate after the total annihilation of the nation, which the military once served. Such cybernetic processes form an inescapable circle of insanity. Each step logically leads to the next, but they ultimately close in a circle. The processes are so intricate and complex that they mask their futility. Additionally, the recognition that the technique is futile or insane can only be made from a perspective that is not on the level of one of the steps of the process, but outside technique altogether. The reader occupies such a position, while the characters are trapped. And the reader feels that this is only a slightly warped, still familiar, world of sophisticated technology: endless fluorescent-lit corridors; television reruns; jobs of data processing that seem meaningless. It is an insane world generated by the tunnel vision of computer science dedicated to a reductive technique in which nature, the unconscious, emotions — in short, human meaning -- is not quantifiable.

This is the cul-de-sac that Lem illustrates again and again: man creates a game which he plays so fanatically that he takes it more seriously than the life which caused it and on which it is dependent as a specialized function. Buddhism calls this heedlessness or ignorance (avidja) and identifies it as the fundamental human problem. Bondage (samsara) is the result of taking the game or technique more seriously than life. Until one awakens to transcend compulsion, there can be only ceaseless incarnations or games; endless corridors and mazes circling back in countless neurotic repetitions.

Such a mechanical paradigm of life is illustrated in Memoirs

when the narrator is conducted through "the Department of Collections," a

kind of nightmare temple, where he sees, "artificial ears, noses, bridges,

fingernails, warts, eyelashes, boils and humps, some displayed in cross section to show

the gears and springs inside" (21). The dream is an obvious one of disintegration,

mutilation and alienation caused by Isaac Newton's machine metaphor, which is unrivaled.

Jacques Ellul explains that human life in such a clock-work universe can only be explained

as engineering "technique"; a cybernetic psychology which considers life events

to be arbitrary steps in a technical process (see Ellul, "Ideas of Technology:

The Technological Order" in Technology and Culture). This view cannot see

the tacit dimension, embodied or performative knowledge, dreams and processes of the

unconscious, not to mention God. Thus the myth of technique sees the origin of

man in a factory of mechanical body parts which can be assembled and disassembled by

surgeon-engineers. The Utilitarian outlook arbitrarily begins with socialized adults,

ignoring how they were produced. There is no depth nor organic process precedent to

consciousness; there is no spirit enlivening and transforming parts (which only have that

identity relative to a whole of which they are parts) into a living unity. Instead of man,

there is Frankenstein's boiler-plate jerking monster. In the story "Doctor

Diagoras" in Memoirs of a Space Traveler, a cybernetic scientist creates

various living systems or creatures which he says "rise from the dead" (128).

Such statements, characteristic of Lem, annul the Romantic tradition and all

biological-mystical thinking from Aristotle's Physics to Bergson's elan vital, to

Hegel, de Chardin, and Whitehead. For these assume -- as does all of Asia (Hinduism,

Buddhism, Taoism) -- that life rises from some vital power which could not possibly be

referred to as "death."

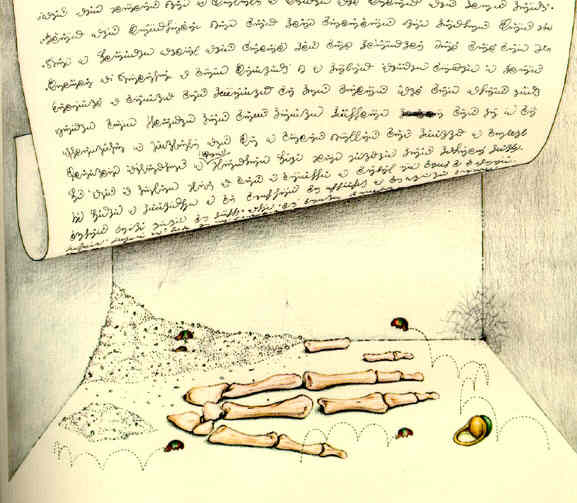

In a related scene at the end of the novel, the narrator walks through a museum of hands: "hands severed at the wrist, often clasped in pairs on their glass shelves, very true-to-life, too true-to-life." There is "a forest of fingers" which suddenly all point to the narrator who feels held by "the numb and bloody hands of madness" (176-77). Because they are severed, the hands can grasp nothing. They illustrate that technique (in Ellul's sense) is severed from life. There is no transcendent end to grasp. The pragmatist, C. I. Lewis observed that, "the content of experience cannot evaluate or interpret itself" (27). Thomas Kuhn, paraphrasing Wittgenstein, further explains why steps in set theory or atomic "factuals" in any technique are inadequate to explain the whole: because they are such steps or "facts" only in relation to the whole, which must grasped as a whole/gestalt, as a concept, or as a word within the universe of language: "We have no direct access to what it is we know, no rules or generalizations with which to express this knowledge. Rules which could supply that acess would refer to stimuli not sensations [much less conceptions], and stimuli we can know only through elaborate theory [set theory, cybernetics, physics]. In its absence, the knowledge embedded in the stimulus-to-sensation route remains tacit" (196). The words and images in Lem's nightmare dream are of castration because they have no background or context supplied by libido, by embodied knowledge in life.

Like Kafka's Joseph K., the narrator wanders the subterranean tunnels of nightmare, entering random doors only to find he is expected as another bit of data to be processed; another "hit" at a website. This leads him to believe that there must be a Master Plan, a master-program, and consequently, a master-programmer. However, on the level of plot, this teleology is frustrated by the knowledge that events are cybernetic "choices" made pursuant to a garbled military strategy which is meaningless because the situation in which it may have made some sense is now entirely changed. This pseudo-mythic cybernetic pattern is a razor that can only mutilate life as it emerges from the unconscious to be patterned in politics, religion, art and labor.

Lem illustrates the fallacy of cybernetic psychology, which always ignores the context it employs, by using atomic bits of data, which are not themselves elementary, but rather the result of human situations which resonate with depth and meaning (Dasein). As a result of human situations, embodied life experience can be abstracted as data/concepts, which are then related by abstract linguistic or mathematical relationships. Making this same point, Hubert Dreyfus notes in What Computers Can't Do: "The human world, then, is prestructured in terms of human purposes and concerns in such a way that what counts as an object or is significant about an object already is a function of, or embodies, that concern. This cannot be matched by a computer, which can deal only with . . . context-free objects" (261). To escape Lem's chains of technique, we need only recognize that truth cannot exist in a vacuum as an atomic, causal principle ripped from the ecology that produced it, to be made into some all-explaining principle, such as economic determinism, the hedonistic calculus of utilitarianism, natural selection, the will to power, operant conditioning, cybernetic technique, or other varieties of scientism. If we consider the pragmatic and postmodern epistemology of model-building (language) as not only the method by which we manifest truth, but also, possibly as life -- the way the Indeterminate, the libido, or as the Hindus call it, shakti, becomes partially manifest -- then we will be less likely to be compulsively and suicidally committed to any reductionism.

Seeking the "Master Plan," the cybernetic logos, to explain his world, the narrator discovers that "everyone wears portable decoders" (36) to analyze every word for hidden meanings. For words in a cybernetic system have only arbitrary and temporary references to each other. Like following the endless words in Borges' "Library of Babel," the narrator walks "alone down endless corridors, corridors that continually branched out and converged, corridors with dazzling walls and rows of white gleaming doors" (37). Rest comes only in a marble bathtub, "like a sarcophagus." But this is not a sleep that renews. For in the myth of technique, sleep can only be "down-time." And if the water in the tub suggests life, the tub is itself like the simulated society of the novel: blank as porcelain. The water may ritually cleanse, but here the towels "are embroidered with staring eyes" (38).

After a bathtub baptism, the narrator enters a guarded door and, as in the mythology of Kundalini yoga, ascends the "spiral staircase" of the spine, finding himself on the "threshold of a dark chapel." Consistent with the pyramid tomb, and the ego it represents, the chapel remains dark; there is no enlightenment nor transcendence. There is a funeral instead of birth: "inside, under a crucifix lay an open coffin" containing the body of a general whom the narrator hoped would prophetically brief him on his Mission (39). In despair, the narrator begs to confess to a monk: "permit me to report" (41). The interchanging of military and religious language and offices indicates a mutual collapse of each paradigm into the other. The focal point of military concern is power/force. The focal point of religion is the meaningfulness of human experience; what the Japanese philosopher Watsuji Tetsuro "betweeness" among human beings. These incommensurate concerns morph into each other creating something like a genetically deformed society.

The reader sees the futility of following the "usual business" within this deformed society. She sees that the structure is beyond repair, because it fails to enhance life, and should be abandoned. However, to those who have never had the experience of living outside the grammar of the crippled paradigm—including the narrator—condemning the familiar, regardless of its failings, seems irrational. One can reject a paradigm only from the perspective offered by another paradigm (Kuhn 77-79); and in the pyramid, there is only one monolithic "operating system" (as in DOS, Unix, NT, etc.). The technique learned by paradigm acquisition defines logic for the community sharing the paradigm. Walter Ong makes an interesting point about how one acquires a language, reminding us that medieval Latin, Rabbinical Hebrew, classical Arabic, Sanskrit, classical Chinese, and Byzantine Greek -- all languages in which world religions have been articulated -- were artificial, i.e., learned by males outside the home, in adolescence, from other men. With no connection to direct life experience, embodied knowledge, or libido, these languages are completely defined by the grammar of writing. Ong then reminds us that "Modern science grew in Latin soil, for philosophers and scientists through the time of Sir Isaac Newton commonly both wrote and did their abstract thinking in Latin" (114). Perhaps we readers are not so far removed from the kind of arbitrarily fabricated world of Memoirs (a text) as we thought.

Those inside the system can see those outside the system only as barbaric, primitive and irrational. In a cybernetic psychology there is no exit, for nothing is acknowledged to exist outside the system. The system either operates or it is shut off. Transcendence is considered annihilation. Thus in the Kundalini scene, when there should be enlightenment and rebirth, there is only a corpse. In contrast, organic psychologies and theologies not only recognize transcendence of logical technique, but normatively define it as liberation or enlightenment. And, despite the collapse of religion into secular politics -- which is as unavoidable in Marxist moral theory as it is evident in capitalistic technique — Lem implies the corrective vision of organic psychologies, such as those of Viktor Frankl or Erich Fromm, which in turn rely on Jung and Freud and finally on Goethe, Wordsworth and Romanticism. It is from this inclusive paradigm, within which these and other organic psychologies exist, that Lem is able to reject Newton's clockwork metaphor repopularized as cybernetic psychology, which considers human life and the mind to be produced in virtually the same way that computers operate to produce simulations.

Frankl can be thought to speak for the humanistic and religious traditions of the West, as well as for Asia, when he says that "human existence is basically unreflectable" (30). Appropriately, Lem has a priest state something of the same sort: "we are as unfathomable, as inscrutable as That which brought us into being, and we choke on our own enigma" (46). Of course, the irony is found by the reader in knowing the reference to "That" is not solely religious but also military. Ironically, this very confusion and multiplicity creates a climate comparable to what Thomas Kuhn calls "science in crisis" when "the rules of normal science become increasingly blurred" (83). Thus our narrator confesses that: "again and again I was given to understand that nothing, really, was expected of me. And that was the only thing I couldn't accept, because it didn't make sense" (109).

Increasingly conscious of "symbolic generalizations" -- " those expressions, deployed without question or dissent by group members, which can readily be cast in a logical form" -- the narrator begins to recognize the epistemic process and discern the difference between a model and what it hopes to interpret (Kuhn 182). Referring to the Master Plan or the logos, he reflects: "just imagine, what if there were more than one plan? Not two, nor four -- a thousand! Ten thousand! A million!" (30). He begins to understand that a paradigm, such as the Pyramid, is one of a number of possible renderings of life experience, which cannot be exhausted nor entirely articulated by any interpretative model: "however far from it our theorizing may soar, it must take off from and return here," to life and the unconscious (Barrett 146). Although the clergy are expert decoders, using "bugged percolators," "polygraph mittens," and "microphone pillows," they have not succeeded in finding the key to crack the Bible code, nor the code of existence. In the cybernetic myth, God, or "The Cosmic Command, obviously no longer able to supervise every assignment on an individual basis when there are literally trillions of matters in its charge, has switched over to a random system!" (54). Opening a tabernacle-safe, the narrator finds only an empty folder. There is no system administration manual; nor is there a Torah, Bible or Koran.

Beginning to realize that technique is endlessly repetitive and narcissist, the narrator reassess human relationships, such as trust. He begins to feel, as Watsuji Tetsuro, says: "Human truthfulness occurs between one person and another. It does not exist ideally and statically in the form of something completed" (279). In a chapter on "Trust and Truth" in his influential work on ethics, Tetsuro says that "Human action cannot, however, take place apart from the presence of trust . . ." (268). Actions lacking or betraying trust are, he claims, not really human actions but only their simulation, which make sense only by recourse to the standard: acts of mutual trust.

Professionally opposed to trust, Major Erms, a military father/robot figure whose name ominously recalls the gallery of hands, offers the narrator a kind of aesthetics of cybernetic technique which appreciates that "everything is a code," which construes trust as moronic gullibility. The activity of consciousness invests sensations and experience with meaning by placing them in a gestalt or a disciplinary matrix. The problem, for finding the unequivocal and absolute Truth, is that the same sensations can be placed in any number of models to create entirely different fields or patterns or meanings. Music illustrates how this process works with the uninterpretable sensation of sound. When conceptual symbols, such as language, are used, the focus switches from grammar and syntax concerns to plot/conceptual concerns. The Major proposes a kind of postmodern analysis which appreciates that "the whole purpose of a code" is to conceal information (60). He evidently does not notice the epistemological difficulty in how to differentiate concealment from disclosure, falsehood from truth. The Major, however, is sensitive to the postmodern sense of grammar and textuality, expressing this with Lem's penchant for science metaphors. The Major claims that the ultimate concealment is one's self. For one is a DNA code, a cybernetic code, a temporal code, and other codes or relationships that ultimately cannot be "cracked" or escaped because one is inside them; one is the result of such various techniques. Moreover, Major Erms says, "a cracked code remains a code. An expert can peel away layer after layer. It's inexhaustible. One digs ever deeper into more and more inaccessible strata. That journey has no end" (65); causing the narrator to reflect, "The Department of Investigation'! Once there, you never leave" (72).

In The Cyberiad Lem observes that consciousness forms "a deadly trap, in that one could enter it, but never leave" (41). This is the flat horizon of cybernetic vision, which cannot imagine transcendence, nor even other equally valid paradigmatic views. Whether one thinks of Providence or natural selection or class struggle, Major Erms explains, "instructions have to be in code," so that although one never understands one's Mission, it is at every moment being implemented (54). At this moment, when the paradox should cause a gestalt shift to recognize deep structures, such as the creative unconscious or Heidegger's Dasein, the narrator remains confined in the only language he knows. Since the narrator is the product of cybernetic psychology, which recognizes nothing of epistemic significance beyond technique, there can be no transcendence. Echoing Nietzsche, he says, "I was beginning to doubt the very, existence of the instructions themselves" (58).

Frankl writes that "in our century, a deified reason and a megalomaniac technology are the repressive structures to which the religious feeling is sacrificed" (70). So even if the narrator were a person ( i.e., produced by trusting relationships with other persons), and consequently embedded in nature and the unconscious (having embodied or performative knowledge that preceded conceptualization), the technological paradigm he professes would repress this recognition, identifying it as primitive emotion without epistemic significance. When something like this recognition threatens, the narrator flees into a bathroom, which has not only the Freudian significance of "coming clean," seeing one's self naked in the mirror, and getting rid of "the shit," but also symbolizes the porcelain surfaces of technology. In the bathroom "everything gleamed . . . with the dazzling cleanliness of an operating room" (68). The surgical metaphor reminds us not only of the severed hands but also of the surgical operation of gazing into the mirror to see who we are before putting on a face for the world. The bathroom also has significance in the light of cybernetics. For in denying the realms above and below what is programmable, the bathroom is the only temple left. It is all shit, i.e., meaningless, worthless. If man is technique, his name must be Narcissus.

Contemplating suicide -- the ultimate negation of the idea that one is simply a robot -- the narrator continues looking for philosophical answers. He goes to the library where in the "murky labyrinth" of books, he comes upon this definition: "ORIGINAL SIN -- the division of the world into Information and Misinformation" (75). There is no way to judge which is which from inside a cybernetic system. From a Christian view -- recall that Lem lived among Nazis in World War Two and argued theology with the Pope -- the entire cybernetic paradigm is imbued with original sin. Reinhold Neibuhr explains: "Reason which seeks to bring all things into terms of rational coherence is tempted to make one known thing the principle of explanation and to derive all other things from it. Its most natural inclination is to make itself that ultimate principle, and thus in effect to declare itself God" (31). Fromm echoes this condemnation: "finally and fundamentally, it is not that the ego has a problem, but that the ego is the problem" (154). Memoirs shows us a world reduced to rationalism, a world extrapolated from cybernetic psychology. It is not Voltaire or Diderot's utopia; it is a nightmare. Lem's vision parallels Polanyi's thesis of how the Enlightenment, and its obsessional reliance on Newtonian mechanics, led to such nightmares of the twentieth century as Nazism and Stalinism. He asserts that "it was not technology that produced the totalitarian ideologies which brought the disasters of the twentieth century into being, along with the feeling of absurdity and the contempt for human society that are current today. We may thank the scientific image of the world, as reflected in the modern mind, for these (Meaning 105; also see "The Eclipse of Thought" 3-21).

Hoping for an authenticating relationship, the narrator finds the priest distant because of his professional technique. He finds Major Erms too Japanese, too aesthetic, and thus also distant. Back in the bathroom refuge, the narrator meets a psychoanalyst-spy who seems more approachable. Because he is also in the bathroom, the analyst does not seem to have an office in the bureaucracy. He seems approachable; someone to trust. In fact the analyst rejects the cybernetic view, professing love as the logos. The narrator's cautious cynicism, in a novel where the patron saint is "Peter Renouncing Christ" (144) -- moves the plot to a distinctly Christian crisis in which the analyst sacrifices his own life to prove that love can break the code, liberating man from programming and the ideology which makes him a robot programmed by technique.

Before the narrator can love or trust, he must break out of the cybernetic paradigm, which in fact, he never does. His faith in the cybernetic paradigm seems to be exhausted in a scene reminiscent of Kafka's The Trial. The narrator is ready to "confess to everything and anything" (109), if only someone is there to listen. But in the cybernetic paradigm, as illustrated by Joseph Weizenbaum's famous psychotherapeutic program, ELIZA, there are no persons. ELIZA was a computer program which simulated psychotherapeutic dialogue with subjects. Although aware that they were interacting with a computer program, subjects still imputed human motives and depth to the "person" they trusted, ELIZA. From Hobbes to Marx, technique creates consciousness and values. Trust, judgment, creative insight, love, conscience -- all of these are epiphenomenal. What the Enlightenment derogated as superstitious did not stop with religious concepts; it included all humanistic and humanizing concepts. Seeing himself in this light, the narrator admits: "all along I was nothing, just one of a series, another copy, a stereotype . . . repeating like a record player exactly the same words, feelings, thoughts. My melodramatic actions, the sudden impulses, false starts, surprises, moments of inspiration, each successive revelation-all of it, chapter and verse, including this present moment, was in the instructions -- no longer my instructions, they weren't made for me" (124). Defining Kant's Transcendental Reason, F.S.C. Northrop says: "Since the a priori concepts are the same for everybody and are formal, it is really not the varied, differing persons who are the knowing egos, but instead a single or what might be termed ‘public ego'" (199). The cybernetic vision is complete when this faith in determinative reason is linked with a faith in atomic facts/bytes as the building blocks of reality. Thus, "the computer serves as a model of the mind as conceived of by empiricists such as Hume (with the bits as atomic impressions) and idealists such as Kant (with the program providing the rules)" (Dreyfus 156). Basing his argument on internal inconsistencies within the paradigm of cybernetic psychology (from a pragmatist position), instead of using glaringly incompatible outlooks, as Lem does with Christian love versus robots, Dreyfus suggests that cybernetics has driven the Western epistemology of Plato and Descartes to a crisis: "the moment has come either to face the truth of the tradition's deepest intuition or to abandon the mechanical account of man's nature which has been gradually developing over the past two thousand years" (79).

The crisis Dreyfus perceives is exactly the crisis that Lem uses his fiction to illustrate: "If the computer paradigm becomes so strong that people being to think of themselves as digital devices . . . then, since for the reasons we have been rehearsing [in the epistemology of pragmatism], machines cannot be like human beings, human beings may become progressively like machines" (280). In Lem's The Futurological Congress, what seem to be robots turn out to be people who, being drugged, think of themselves as robots (136). The narrator of Memoirs admits: "I found I couldn't even think, someone was doing it for me" (151). Having recognized technique, we expect the narrator to be liberated from it, to turn to persons in dialogue, trust and love. But liberation must come from something deeper than conceptual recognition. Moreover, liberation is not merely a shift to an alternative paradigm, a reincarnation. A professor in the Pyramid explains that to ask about meaning is already to enter the corridors of technique/grammar. From this view, liberation is "quite simple, really, the taking away of meaning." Like a Zen monk, the narrator must "methodically, with the utmost care . . . deprive everything, absolutely everything, of its meaning." He must cease to: 1) have some experience; 2) conceptualize it; 3) process it as data in the appropriate domain; 4) then derive appropriate (rational) behavior from the model. The Zen monk is thought to be enlightened and liberated when he simply acts without first conceptualizing the Confucian context (e.g., a relationship between husband/wife, employer/employee, master/disciple) and then following the authorized script for appropriate behavior. As a Westerner, conditioned by Hume and Kant and the cybernetic vision, the narrator sees this as only "a kind of destruction" in this (149).

Since the narrator is trapped inside the Pentagon-pyramid in Cheyenne Mountain, he cannot ascend the mountain; nor does he transcend the psychology of John Locke and B. F. Skinner. He does discover that truth is always model-relative and cannot exist apart from the field or gestalt which manifests it. He discovers that the process of de-mythification simply provides a new, and again unrecognized, myth. So-called deconstructionalist writers simply author new texts to keep us reading.

The narrator learns that since there are multiple and competing paradigms or sciences, there will always be paradox, ambiguity and indeterminacy. Additionally, concepts grow "obsolete in time," and are "eventually lost, yet how" can "the following generations discard their heritage?" (149). Because they are deferential to their parents and grandparents, rituals become codes; life becomes technique. Finally, the narrator perceives the awful skepticism inherent in cybernetic psychology. Lem conjures a cybernetic-age lvan Karamazov who argues for nihilism: "The thought that your suffering might be incidental and not intentional, that no one takes an interest in it, not even a sadistic interest, for the simple reason that it concerns not a soul but yourself --surely that's an unbearable thought." Consequently, one invents God and "Mystery offers a way out, a way out of all monstrous absurdities. With Mystery, one can at least hope" (168). But the skeptic leaves no hope: "take a million pieces of gravel like this, a trillion, and an atmosphere will form around them, the wind will blow over them, and cosmic rays will bombard them -- until from out a pile of debris there will crawl forth something we call -- Sacred . . . . And who gave the order? It is exactly the same with the Building . . ." (170).

We are so used to these reductive physical science arguments, which deny the very teleology they use, that we rarely oppose them. Epistemologists, beginning with Hume and Locke and Hobbes, broke human experience into atomic bits and then decided that the bits were more fundamental than the whole. They supposed the bits built up the whole, but all they did was dissect the whole into bits. Whether or not these bits randomly coalesce into a whole, such as Lem's skeptic argues, is far from proved. Moreover, as Dreyfus and Barrett and Rorty and others from the pragmatist outlook remind us, "we do not directly perceive the world of atoms and electromagnetic waves" (Dreyfus 268; cf. Kuhn: "people do not see stimuli; our knowledge of them is highly theoretical and abstract," 192; "We do not see electrons," 196; they are concepts). We inhabit a world of human situations (cf. Heidegger's Dasein); and the interpretation of these situations -- which is not a model but life itself -- through specialized paradigms/terminology, is not primal, but highly abstract and formal. Formal in the sense that the relationships do not arise directly from life, but from relationships specified by linguistic and mathematical systems. Consequently, it is an inversion, caused by the pervasive ideology of technique, to assume that the special vision, seen through the lens of the rarified paradigm, is more fundamental than what we know from human relationships.

Having destroyed the narrator's faith in the pyramid, the priest offers love: "Wisdom is you, yourself -- or maybe two people!" If the narrator is to become human instead of a hologram or some other such simulation -- a voice, an author -- he must deny an ultimacy to objective things and recognize his own subjectivity as the ground or field in which all meaning exists. A more fundamental process than the calculation of the "ego," (which represses its origin in socialization; the cry of "me" against "them"), it requires another person to experience trust, friendship, love. And if these become central in a life, then technique is powerless, because it will be seen to deal with inconsequential, objective data. This is the position advocated by Christian philosophers of technology. Thus Ellul says, man "can inquire after the values to impose on techniques in his use of them, and search out the way to follow in order to remain a man in the fullest sense of the word within a technological society. All this is extremely difficult, but it is far from being useless, since it is apparently the only solution presently possible " (400). Pragmatists and many postmodernist would locate the saving knowledge in the ability to shift from one paradigm view to another so that one is not a cipher in any lockstep logic (including Christianity). To forestall this, the Bureaucracy encourages spying, complex technique and oppression.

The priest proposes the ultimate conspiracy, unconditional mutual trust, love, between himself and the narrator. Since the plot is a nightmare, adolescent discovery of an alternative self, a lover, is doomed. Instead there is adolescent crisis, manifest in such dream images as: elevators going up and down, like uncontrollable erections; noise in the bathroom pipes, which threaten sexual embarrassment; and the mechanical fingers and severed hands that suggest dildos or vibrators. The only woman in the book is encountered in a nightmare rape scene. The act is a calculated attempt by a juvenile to create an image for himself unilaterally through force instead of trust: "I was a Bastard, proud but a little bashful" (181). It culminates in revulsion when, having dominated and depersonalized the girl, he tries to experience love and sees only body parts or body lubricants: "Passion!! Lust!! I swooped down -- something was wrong -- her mouth was full -- white -- a whiff of -- of -- what? Cheese! Cream cheese!!" (183).

Love between the narrator and priest is even more impossible, because, to be anything more than juvenile homosexuality, it would have to be abstracted from more comprehensive and mature experiences of love. I am not denying homosexual, loving relationships in principle, only saying that in the nightmare world of the novel, where, e.g., no one seems to have a mother, homosexual love and trust is at least as unlikely to blossom as heterosexual love and trust. In fact the impossibility of trust and love between persons of any gender and age is exactly the problem. Self-infatuated (the condition of original sin), the narrator refuses the risk involved with trusting and loving either persons or God. He imagines, "cross and double-cross," maybe "a Grand Inquisitor," nails, thorns and "a spear in the side" (180).

In despair he chooses suicide by leaving the only reality he knows, the mountain-womb. But before he goes, he visits the bathroom to tell the analyst his decision. There he discovers the analyst's corpse. Initially this, like the Kundalini scene, implies that there can be no love, no transcendence, no birth from the unconscious into consciousness. Still conditioned by his life-long cybernetic epistemology, the narrator looks for a rational message to explain this event. But there is no note, "only a naked body, as if to say by the very nakedness of death that not everything was false, that there was in the final analysis, something that no amount of subterfuge could ever alter." But the answer is not the stark facticity of death, it is the ambiguity and struggle of love. In this dream-cauldron world, the narrator believes that, like Christ, the analyst "died, then, for my sake" as "the only way to convince me that he hadn't lied" (187). The narrator believes that he died to give life, and trust in life, to the narrator. Tragically this is only another conception, another word, another text, another circuit and dream inside the tomb of the Pyramid. Life requires persons and there are no persons in the Pyramid; only a text and a simulation. Consistent with the possibilities of the fictional experiment, and more than a little indicative of our medieval-like faith in the cybernetic vision and involvement with computers, Lem cannot allow the narrator an escape. If he did, all the philosophical angst, caused by epistemological puzzles, would evaporate. We would supposedly know the answer. And the whole point of the book is to illustrate the impossibility of knowing the answer. Our narrator remains in the mountain-tomb, an aborted life, a adolescent suicide. There is no love and hence no life in simulated situations.

The historian who introduces Memoirs tells us that two skeletons were found in the bathtub, along with the book, suggesting a parody of a lover's suicide pact. In rejecting love, the world came to an end. Lem's illustration of the cybernetic world-view as nightmare can be read only as criticism of cybernetic psychology. This view is supported by rereading the introduction in which the historian remarks on computers of our age: "They were called ‘electronic brains,' an exaggeration comprehensible only in the historical perspective, much like the boast of the builders of Asia Minor, that their sacred temple Baa-Bel was ‘sky reaching"' (1). Certainly this is condescension from the height of a superior technology. We assume, however, that man did reject the cybernetic paradigm because of the dramatic situation in which the historian writes of a lost and presumably more primitive civilization.

Where does this leave Lem? It does not leave him, as many critics think and as Lem himself often proclaims, an advocate of cybernetic reductionism. Quite the reverse; dramatizing its flaws, Lem is not inside the paradigm, but immediately outside looking in. This is similar to Luther's position: outside the monastery, and thus able to see its limits.

At one point in Memoirs, the narrator visits a hermitage which seems like a dream within a dream. It is "cluttered with all sorts of junk -- dirty sacks, onion skins, empty jars, sausage rings, ashes and old papers." The images are mostly of empty containers. In the cell, "there was shuffling, whispering," and "shadowy figures" that "scurry about, crouch in the corners, scuttle under crooked tables or cots"; instead of contemplation and wisdom, "there were angry whispers and grunts in the darkness" (45). In images and associations like these -- and religious images are manifold in his work -- Lem illustrates the pathetic position of man today: looking for meaning in the cybernetic maze of his own making.

Christianity, especially in its Protestant principle of denying the absolute in any relative system, is certainly capable of resisting the cybernetic vision. Indeed, Jacques Ellul, Egbert Schuurman, Hans Kung, and many other Christian writers have identified the problem. Frederick Ferre's book, Shaping the Future, is one of the few positive attempts to write a theology -- still only notes -- cognizant of the pragmatism of Polanyi, Kuhn, and its opposite, the psychology of cybernetics. Typically, Ferre advocates process theology, which has not clearly demonstrated that it can resist collapse into the cybernetic vision. It simply asks for faith that process is not random and circular, but moving toward some eschatology. Bonhoeffer, and the so-called "death of God" theologians, offer an even less promising scheme of retaining the Christian myth in abstract: a discipleship, as Bonhoeffer said, "void of all content" (62). It is difficult to see how either system can avoid invoking a rootless mysticism to escape skepticism.

In a study of Mortal Engines, another of Lem's dramatic speculations on cybernetics, I suggested that Lem refers to Buddhist psychology as an alternative to cybernetic psychology. Buddhism is especially attractive because it shares more of the cybernetic view than Western systems, most notably exoteric Christianity and Utilitarianism, which defend the primacy of the self. Although Lem is himself too much at home in Western science, philosophy, and religion to delve very deeply into Eastern thought, he does suggest -- if in no other way than by demonstrating the cul-de-sac of Western scientism -- that we need some culture of depth recognition to avoid becoming robots and avoid the mono-dimensional programs which have claimed a hundred million murder victims in the twentieth century. In this sense, Stanislaw Lem's work may come to be seen as part of the wisdom of the negative way which unplugs the computer by causing man to laugh at himself and his games, and to love more deeply than he calculates.

Works Cited:

Adams, Henry. The Education of Henry Adams. New

York, 1918: 451.

Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition. Chicago, 1958: 22-78.

Arendt. The Life of the Mind. New York, 1971.

Barrett, William. The Illusion oj Technique. New York, 1978: 105.

Bonhoeffer, Dietrich. The Cost of Discipleship, rev. ed. New York, 1959.

Campbell, Joseph. The Flight of the Wild Gander. New York, 1951.

Campbell, The Hero With a Thousand Faces. Princeton, 1949: 259.

Campbell. Masks of God: Oriental Mythology. New York, 1962.

Campbell. The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology. New York, l959.

Dreyfus, Hubert. What Computers Can't Do, 2nd ed. New York. 1979.

Engel, Peter. "An Interview With Stanislaw Lem: The Missouri Review, 7, 2

(1984): 218-37.

Ellul, Jacques. "Ideas of Technology: The Technological Order." trans. John

Wilkinson, Technology and Culture, 3 (1962): 394-421.

Federman, Raymond. "An Interview with Stanislaw Lem," Science-Fiction

Studies, 10 (1983): 2-14.

Ferre, Frederick. Shaping the Future. New York, 1976.

Frankl, Viktor. The Unconscious God: Psychoanalysis and Theology. New York, 1975.

Fiedler, Leslie. "Travelers in Space and Time," Quest, 1, 2 (May-June

1977): 79-82.

Fromm, Erich, D. T. Suzuki, and Richard DeMartino, Zen Buddhism and Psychoanalysis. New

York, 1960.

Heisenberg, Werner. Physics and Philosophy. New York 1958.

Innis, Harold. The Bias of Communication. Toronto, 1951.

Jarzebski, Jerzy. "Stanislaw Lem, Rationalist and Visionary," Science-Fiction

Studies, 4. 2, (July 1977): 126.

Kuhn, Thomas. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, 2nd ed. Chicago,

1970.

Lem, Stanislaw. The Chain of Chance. Trans. Louis Iribarne. New York, 1978.

Lem. The Cyberiad, trans. Michael Kandel. New York, 1974.

Lem. The Futurological Congress, trans. Michael Kandel. New York, 1974.

Lem. Memoirs of a Space Traveler: Further Reminiscences of Ijon Tichy. Trans. Joel

Stern and Maria Swiecicka-Ziemianek. New York, 1982.

Lem. Memoirs Found in a Bathtub. Trans. Michael Kandel and Christine Rose. New

York, 1973.

Lem. The Star Diaries. Trans. by Michael Kandel. New York, 1976.

Lewis, C. I. Mind and the World Order: Outlines of a Theory of Knowledge. New York,

1929.

Lovekin, David. "Technology as the Sacred Order," Research in Philosophy and

Technology, vol. 3. New York, 1980: 203-21.

Mann, Thomas. "Freud and the Future," Life and Letters Today, 15,5

(Autumn 1936): 89.

Michaelson, L. W. "A Conversation with Stanislaw Lem," Amazing (Jan.

1981): 116-19.

Neibuhr, Reinhold. The Nature and Destiny of Man, vol. I. New York,

1942.

Northrop, F. S. C. The Meeting o/ East and West. New York, 1946.

Ong, Walter J. Orality and Literacy. London, 1982.

Organ, Troy Wilson. The Hindu Quest for the Perfection of Man. Athens, Ohio, 1970.

Polanyi, Michael. Knowing and Being, ed. Marjorie Grene. Chicago, 1969.

Polanyi. Science, Faith and Society. Chicago, 1946.

Polanyi and Harry Prosch. Meaning. Chicago, 1975.

Rorty, Richard. Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge, 1989.

Rothfork, John. "The Ghost in the Machine: Stanislaw Lem's Mortal Engines,"

Liberal and Fine Arts Review, 4,1 (Jan. 1984): 1-18.

Schuurman, Egbert. Technology and the Future: A Philosophical Challenge. Toronto. 1980.

Tetsuro, Watsuji. Watsuji Tetsuro's Rinrigaku: Ethics in Japan. Trans. By Robert E.

Carter. SUNY, 1996.

Vahanian, Gabriel. God and Utopia: The Church in a Technological Civilization. New

York, 1977: 23.

Weizenbaum, Joseph. Computer Power and Human Reason. San Francisco, 1976.

|

S. Lem |

![]()