8.23.2024 AI for dummies

I just heard an ad for C3.ai, one of the many generative AI companies that are springing up in recent years. They toss out a bunch of terminology that may sound impressive but most people have no idea what they are talking about. So here's a very basic primer on AI jargon and what it means. LLM Agnostic: LLM stands for Large Language Model. For AI to sound human, it has to use language the way people do. By dumping lots and lots of content samples into a system that the software can peruse, they are simulating the way people talk. The agnostic part means that the AI in question can use more than one LLM, so that, for example, it can generate convincing jargon associated with biomedical, or legal, or whatever specialized field is needed. IP Free: IP refers to Intellectual Property; specifically the copyrighted original work belonging to other people. What the AI people are saying is that the content that the AI generates is so churned up from various sources that it doesn't appear to violate any one individual's work. I say "appear" because these systems don't actually think or generate novel content. They just rehash from the available source material. But to catch them at it is nearly impossible. Hallucination Free: this is kind of a funny one. You may have heard that while the AI can in many cases do a pretty good job, it occasionally gets things very wrong. A great example is the fingers problem. When the AI is asked to draw people, it often gets the number of fingers wrong. Sometimes background faces in a group photo look like something from Edvard Munch's "The Scream". That's the hallucination. In other cases, faces may look too perfect, with no blemishes, freckles, wrinkles, or features that are out of perfect proportion. These are amalgams of many faces, averaging out the minor individual deviations from the norm. In any of these cases, there's a good chance the image is AI generated. That said, it is getting harder to tell AI from real. Take this quiz to see for yourself.

Here are a few great examples where the AI got it wrong:

This group photo of female F-35 pilots looks good at first, but zoom in on the ladies in the back row on the right. It gets worse...

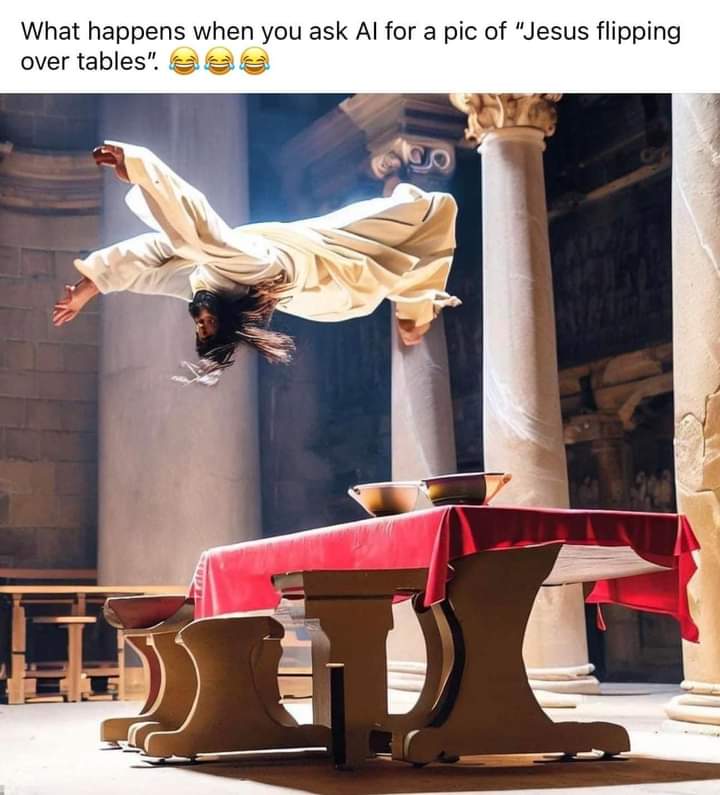

If you're familiar with the bible story of Jesus flipping over the sellers' tables in the temple, I don't think this is what was being implied. One more, just for fun...

Thus the majestic salmon complete their long journey, swimming back to their natal stream to spawn.

10.24.2023 The COVID backlash - out with the baby and the bathwater!

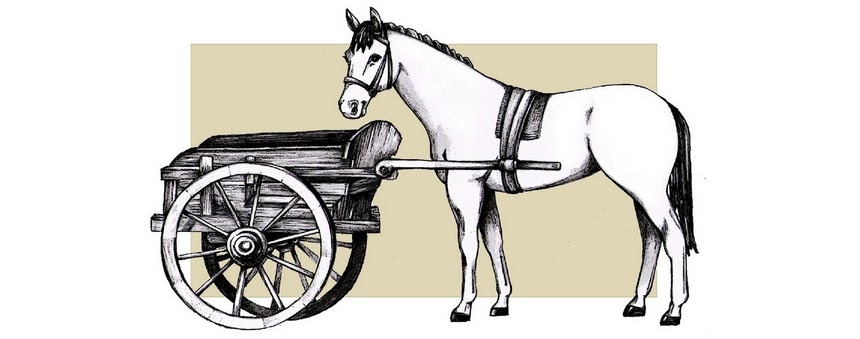

When COVID hit higher education, back in early 2020, a lot of higher-ed upper-level administrators, many of whom didn't have much experience with fully-online education, were asked to quickly come to a decision about how to handle this challenge. Unfortunately, the decision makers didn't take the advice of the people who were experienced in onine education. This is not a criticism of just my own institution, but rather a broad overview of academia's response. I think it's worth exploring why they didn't take the advice of the experts, and looking at some of the major downstream consequences that resulted.

Our advice was to move most courses from in-person to online asynchronous, relying primarily on the Learning Management System (LMS). One reason was the concern about inadequate bandwidth for some of our students, many of whom live in rural Arizona and on the Navajo and Hopi reservations where Internet connectivity is always slow and often spotty. Moving to asynchronous assignments would have reduced the time stress on students who may have been dealing with non-academic challenges such as caring for sick relatives or recovering from illness themselves. The LMS functions well at lower bandwidth, and when students are not all hitting the system at the same moment in time. We recommended the use of tools like Zoom and Collaborate only for lower-stakes activities such as office hours, and promoted our streaming media system, Kaltura, for recording short video lectures that could be buffered and viewed at lower bandwidth.

The second reason is that remote synchronous instruction (mediated by tools like Zoom and Collaborate) is a high-risk strategy because, if the technology fails, there's no safety net. So called "Zoom school" is what many institutions settled on. In the early days of COVID, those failures happened a lot. Zoom bombers disrupted classes, students dropped the call frequently, mics were often muted while people were trying to talk, or unmuted when they were supposed to be quiet, resulting in a lot of awkward and embarrassing background noise. For those who didn't use a false background, the goings-on behind the camera were also sometimes very distracting. Some of these problems can be chalked up to the inexperience of the instructors and support staff with regard to this new mode of instruction. Eventually better security measures prevented uninvited guests from disrupting classes, instructors got better at muting and un-muting participants at the right moment, and at simultaneously monitoring the chat while lecturing. We also started recording lectures for those who dropped out, but they were seldom viewed, and we have the analytics to prove it. Without a doubt, engagement suffered. Many students turned off their cameras and more just stopped attending. Why? Again, the lack of preparation for this style of instruction was a factor. In a lecture hall, the captive audience has little choice but to sit there and listen. Although breaking up the content into small chunks, and embedding regular engagement activities is a good practice for both in-person lecture and Zoom instruction, it's less conspicuous to tune out with Zoom, and not to get called on it.

Some institutions, ours included, went even further, and adopted a variant of HyFlex instruction. Without the staff and technical resources to support it properly, which few schools invested, this meant simultaneously teaching to an in-person and online audience without a lot of help. For most of our instructors, who had no experience teaching remotely, this was the most difficult thing that could have been assigned to them, and the quality of teaching slipped dramatically. It was especially painful for the remote students, who often got forgotten. It's easy to accuse the students and say they should have stuck with it and been more participatory, but the reality is that they were also unprepared for this rapid adjustment.

So why didn't administrators at more schools choose to shift from live, in-person to online asynchronous, as the experts in online teaching and learning recommended? I think one answer is that these administrators falsely believed that asynchronous instruction was "not as good" as synchronous, and feared student attrition. Or, for those who did have confidence in asynchronous, they still feared that the parents and students felt that way, and wouldn't be willing to pay for it. They wanted to change things as little as possible, and made the false assumption that remote synchronous lecture via Zoom would be the smallest change they could make.

Unfortunately, almost everyone looks back on Zoom school and Hyflex as disasters and, in many ways, they were. But one has to wonder about the path not taken. Yes, more change up front would have been necessary, but I truly believe that had we chosen the bolder path at the beginning, we might not now be throwing out all of online education, baby and bathwater. The big winners from COVID seem to have been the for-profit online schools like GCU and SNHU, who stuck to what they were already doing well.

If we don't learn from our mistakes, we are bound to repeat them. One of the other take-aways from allowing employees to work remotely when it's possible, and monitoring them based on performance metrics rather than time in seat, is that employee satisfaction was higher and productivity didn't suffer appreciably. So why are we forcing employees to come back to the office if they can do the job from anywhere? While I think a lot of people want things to "return to normal" and, by normal they mean pre-COVID, the world has changed, and I think we need to embrace that.

10.22.2023 ChatGPT and the AI Panic

In academia and beyond, ChapGPT has been creating quite a firestorm. Although contract cheating (where you pay someone else to do the work for you) has been around awhile, getting the computer to write a passable essay is new. What has got academia in a twist is that writing essays used to be something that made cheating more difficult, and it was always considered the gold standard on ensuring that students "know how to think." Faculty who were disparaging of multiple choice tests have, until recently, felt secure in the belief that requiring students to write essays allowed them to uphold academic integrity. Although this may have always been a questionable assumption, it is now a more dubious claim then ever.

I wanted to see for myself just how good the software is, so I picked a topic I know a fair bit about, set up an account in just a few seconds, and asked ChatGPT to write me an essay on the subject. I asked ChatGPT to write an essay on the topic of Natural Selection (Biology). The essay was generated on the fly within about 10 seconds and, had a student submitted this work to me, with proper references, I would have shed tears of joy and assigned an A+. Even more amazing is that if I click the Regenerate button, it writes a new essay on the same topic that is just as good!

One of the criticisms I've heard about this tool includes the claim that while the AI makes a convincing argument, it does not do a good job of sticking to the facts. In my test, that was not the case. The information was accurate and written in the everyday language that I would expect a good college student to be able to produce. So, in other words, I would have absolutely no clue that this essay was machine generated.

Good news/Bad News. The good news is that an entire cottage industry of AI detectors has sprung up to respond to this new challenge. The bad news, however, is that the tools for detecting AI generated content are really in the same boat as we are. Between false positives (Looks like the student used AI but he didn't.) and false negatives (Looks like the student didn't use AI but he did.), the tools are essentially worthless. OpenAI's own tool for detecting AI generated text gets it right 26% of the time, but also incorrectly identifies student generated text as AI-written 9% of the time. It would seem that Frankenstein has lost control of his monster.

What to do? I expect that while the detection tools may get better, so will the AI's ability to evade detection. There's probably no winning this arms race. Some will pretend that nothing has changed and that everything's fine. Others will hit the panic button and come up with extreme solutions. One option would be to ban all technology and have students write their essays in controlled labs or in proctored online settings, where access to these tools is restricted. Another approach would be to lean into this new technology and have students fact-check and provide references for the AI generated content. But there's a middle of the road alternative that may be more reasonable, although it's going to require some effort. An instructor can do one-on-one interviews with students after they submit their essays, live or via Zoom, and ask them questions about it. It won't take long to learn whether they know their stuff or not.

09.28.2022 What do floppy disks and women's colleges have in common?

What do floppy disks and women's colleges have in common? Your first response might be that both are obsolete, but no, I don't think that's right. There was an article on NPR the other day about the "Floppy Disk King." Tom Persky describes himself as the "last man standing" in the floppy disk marketplace. While sales of floppy disks have been declining for years, there is a niche market for older equipment that still uses this reliable but obsolete technology. Think about voting machines or scientific/medical instruments for example, that serve a very specific role, are expensive to replace, and work just fine except for the fact that the world has moved on. As Tom's competitors exited the marketplace, he found himself in a niche market that, for him, was actually growing. Demand may be low, but it's solid and, without competitors, he's got a monopoly. I heard another article about a womans' college that was yielding to economic pressures and opening up enrollment to male students when it occured to me that it's a similar problem. Many colleges, not just womens' colleges, are seeing declining enrollment, and the solution for administrators is to bring in more students by whatever means necessary. For administrators of womens' colleges, the low hanging fruit may appear to be admitting men. However, the unique value proposition of a womens' college is ruined by that change. Many of the faculty, prospective and current students, and the alumni of that institution are not happy about the change, and this may result in unanticipated attrition of female students, loss of good faculty, and loss of alumni dollars, which may erase any gains made by admitting men. If a university president of a womens' college was to take the opposite approach, to hang on, advertize that uniqueness, appeal for support from alumni to preserve the tradition of single sex education for those who want it, and to scoop up the students from other womens' colleges that are folding or going co-ed, this may be a better long term strategy for success than becoming just another generic university in an already crowded, competitive market.

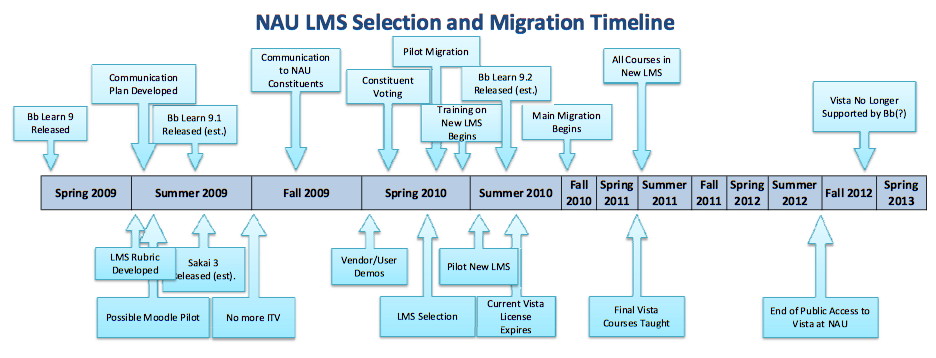

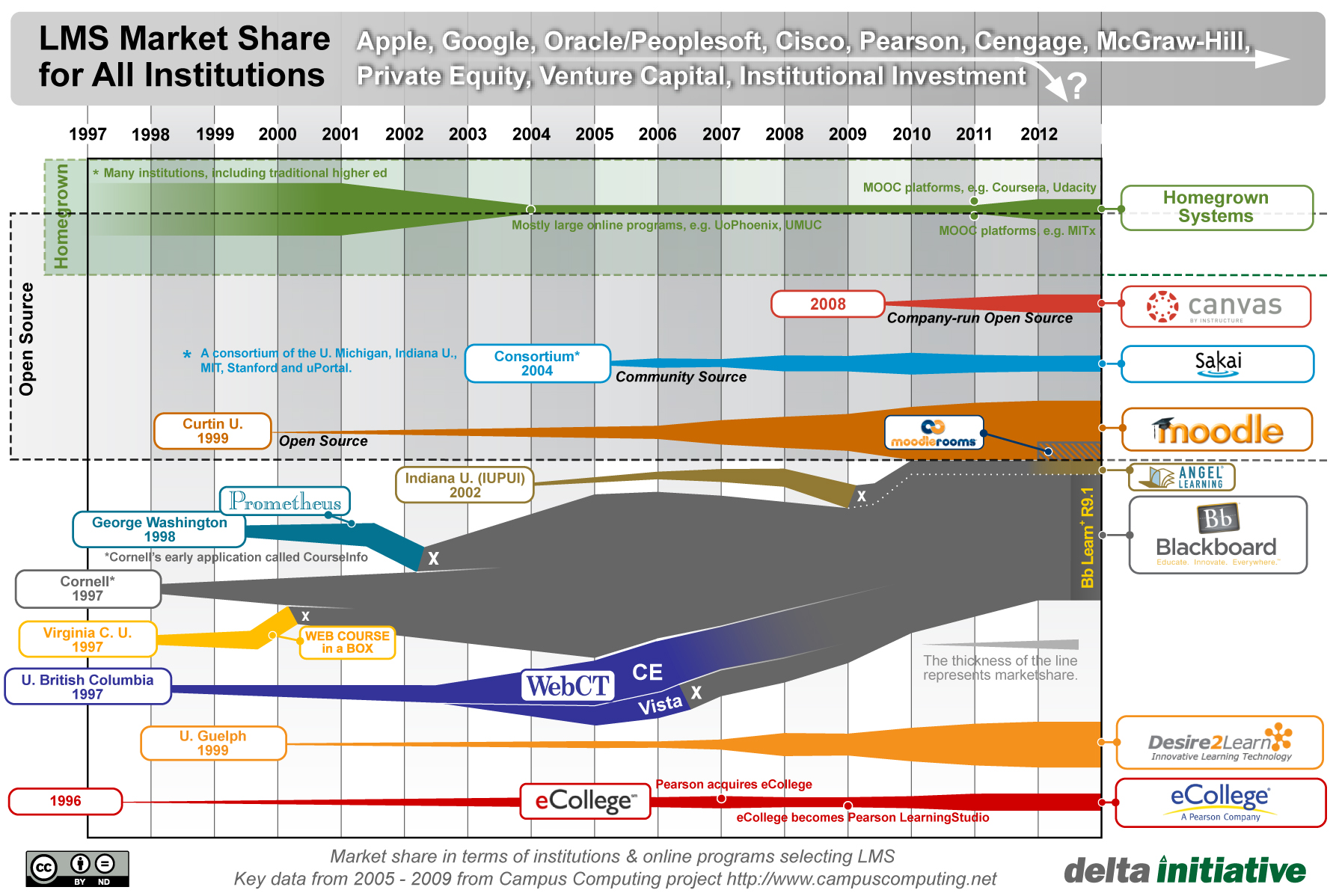

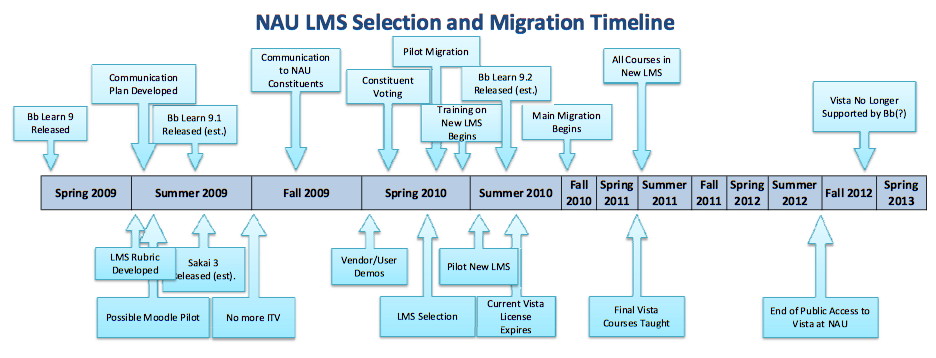

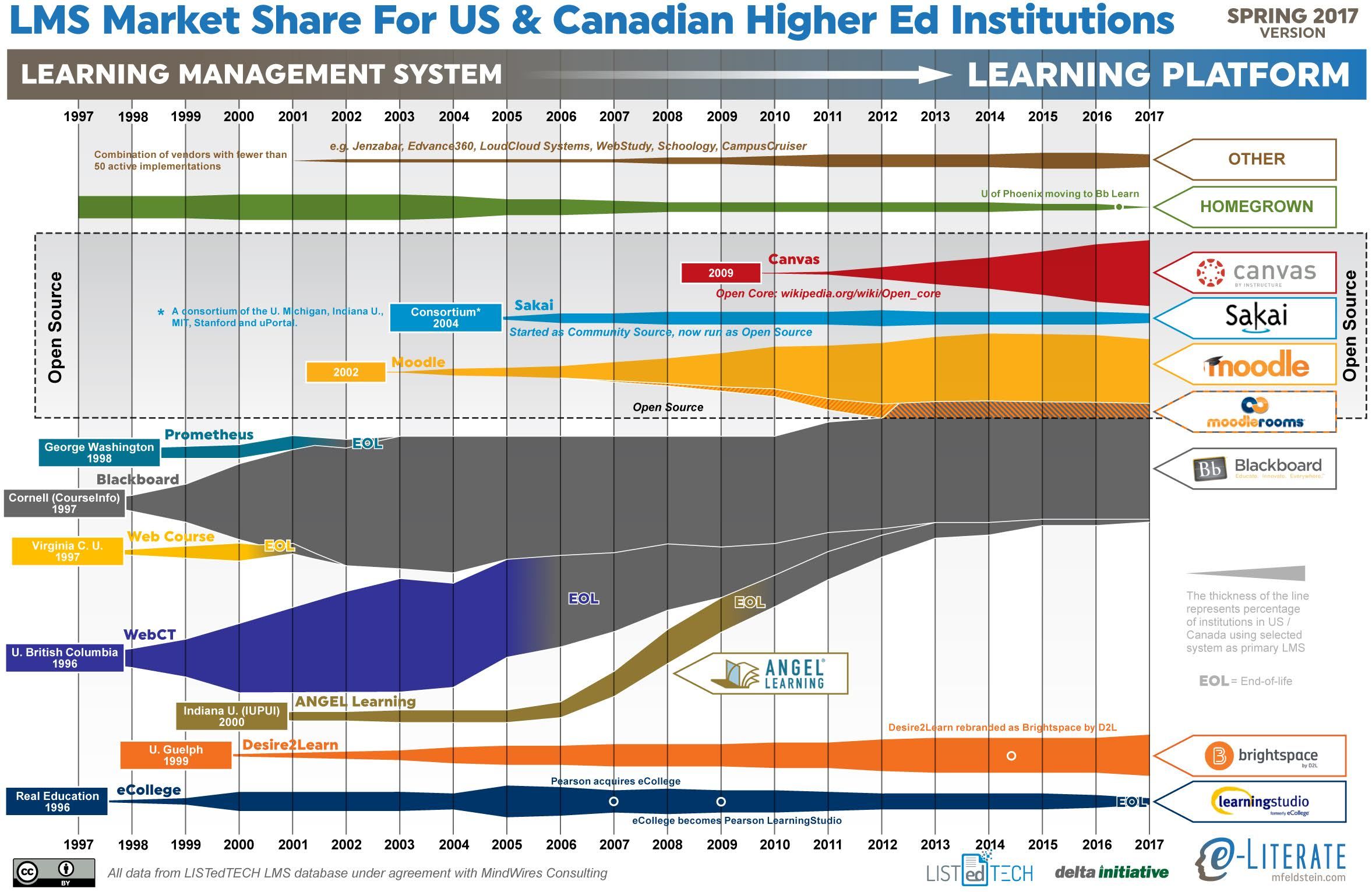

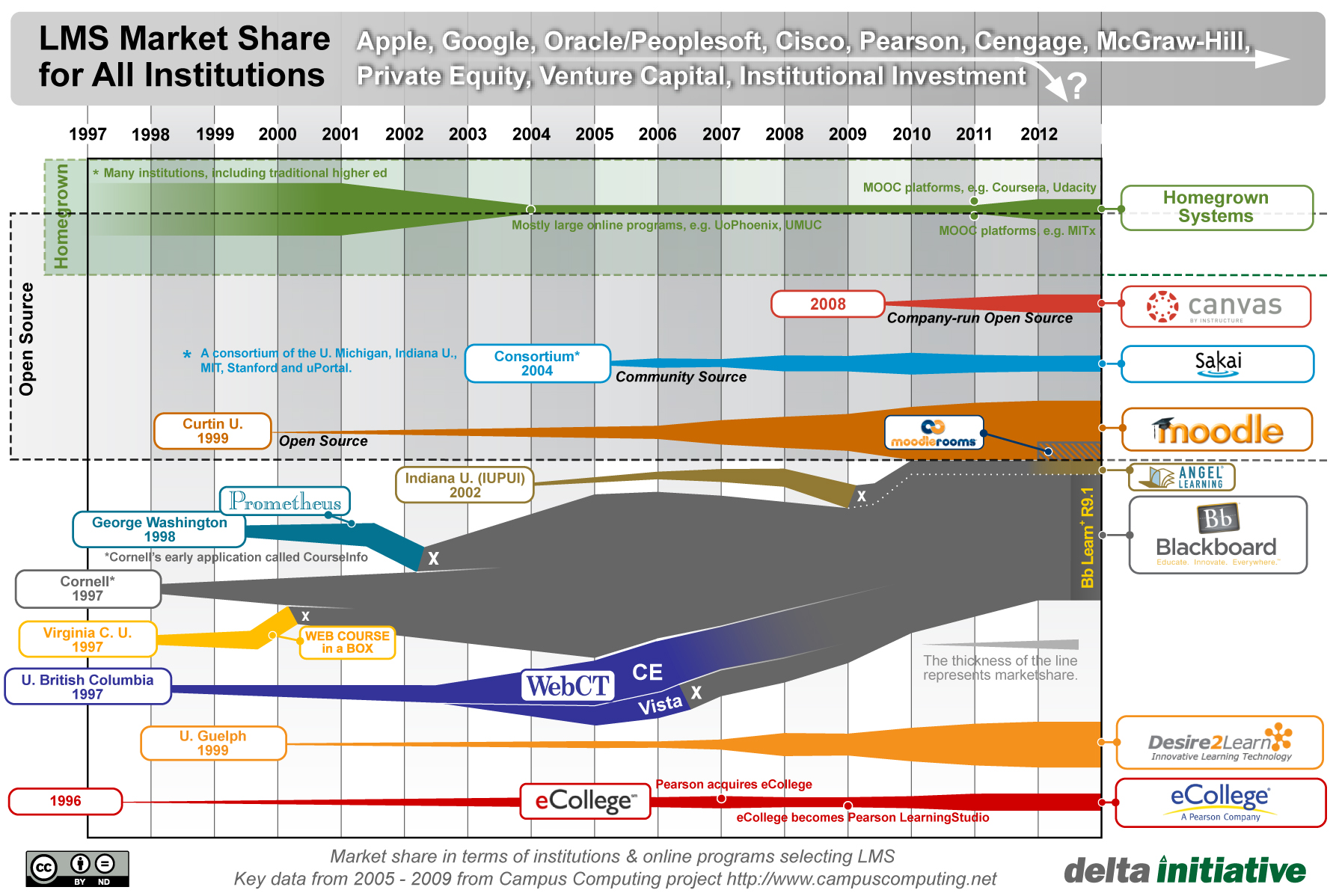

08.16.2022 Picking NAU's next LMS

Recently, NAU decided to begin the search for our next Learning Management System. We are currently using the venerable Blackboard Learn for most of our online courses, Moodle for our Personalized Learning programs, and LifterLMS for enrollment in our Continuing Education programs. Getting to a single, modern LMS is something I've been advocating for several years, and it's finally underway. This is a large and ongoing effort involving a lot of people, both technical and academic. We first had to identify some potential candidates, and pretty quickly settled on Blackboard Learn's successor, Ultra, D2L BrightSpace, and Instructure's Canvas as the three alternatives. Our sister institutions, Arizona State University in Phoenix, and the University of Arizona in Tucson each went their own way, with ASU on Canvas and UA on Brightspace. Our local Coconino Community College, CCC, and the Maricopa community college system are also on Canvas. The for-profit, fully online University of Phoenix was an early adopter of Blackboard Ultra. We met with representatives from each company, viewed their demos, built a criteria list, offered faculty sandboxes to explore, and then put it to a campus-wide vote. In my personal opinion, though it is one that all of the Instructional Designers concurred with, there were two excellent options; Brightspace and Canvas, and one less good one, Blackboard Ultra. I studied all three systems in depth, and developed a page that contrasted the most important features of all three. Of the three, Brightspace is my personal favorite because it has lots of customization options, it is highly intuitive, it is visually the most attractive, and the support/sales people were really great. Interestingly, the vote came back very heavily in favor of Canvas, with Blackboard Ultra a distant second and Brightspace in third place. You can view the results here. Why? Faculty and students outnumbered other voting groups and both of these groups have heard, by word of mouth from peers at other institutions, that everyone else is using Canvas. There is some truth to that, and I think that was enough to convince most people. Another faction, while unhappy with Blackboard Learn, believed that moving to Blackboard Ultra would be less work than going to a different product, though from our research that opinion appears to be incorrect. While I'm surprised that Brightspace didn't win more people over, most really didn't look at the choices in detail and it was the least well known. Don't get me wrong. Canvas will be a fine LMS for NAU, and will be much better than what we have now. But it is far from perfect, and D2L is, in my opinion, putting the most energy into building the best LMS money can buy. Blackboard Ultra is headed in the right direction, but it still feels buggy and unfinished after years of effort and, at the rate that Blackboard is losing market share, I worry about the financial stability of the company. So we will be moving to Canvas next Summer, with the help of K-16 Solutions as a migration consultant. After over a decade on Blackboard, it will be interesting times ahead.

06.22.2021 Life in the time of COVID

Oh, hi, you're still here! Well this has been quite a strange interlude, hasn't it?

When COVID-19 hit the U.S. in March of 2020, my office got busy helping to develop what became known as the NAUFlex (a variation on Brian Beatty's HyFlex) model of instruction. We have, for many years, supported the use of online tools for face-to-face classes, a model we call "web-enhanced." We've done the same for fully online asynchronous instruction using Blackboard and its predecessors (and Moodle for our Personalized Learning program) dating back to the early 1990s. However, live synchronous online instruction was something we had mostly avoided for reasons I'll get into below, but demand grew rapidly, and we had no choice but to dive in. We immediately expanded support for teaching with conferencing tools like Zoom and Collaborate, with Kaltura for streaming recorded media, and with collaborative productivity tools like the Google Apps for Education and (ugh) Microsoft Teams. We were able to convince a few people that uploading PowerPoints and 90-minute lectures was not the best pedagogy. One of us even dropped a best selling book at an opportune time!

Attendance at our webinars increased by an order of magnitude (be careful what you wish for!), and we received lots of positive feedback about our support. This has been an incredibly difficult year, where our personal and professional lives have been compressed into one, with kids and pets and spouses all locked in with us, but a year we’ve come through about as well as we could by being patient, accommodating, and by working together to address the many unexpected challenges our faculty and students have been facing.

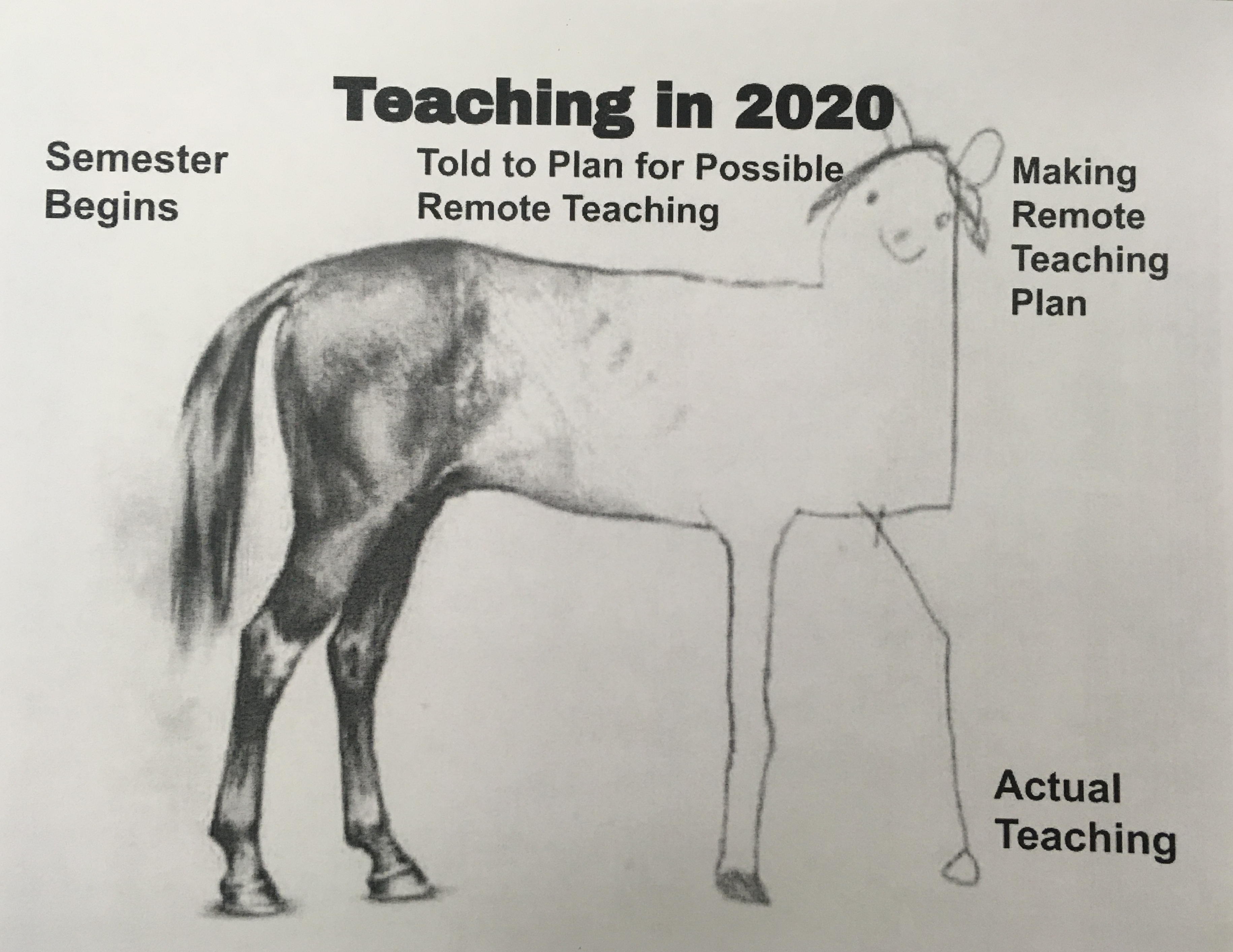

Teaching live online is a hard thing to do well; it's trapeze work without a net. If anything goes wrong in the technology layer, everything comes crashing down. And pedagogical things that are simple in the classroom (everyone break up into groups of five) are clunky at best with our conferencing tools. We endured bad lighting, questionable attire, mouth breathers, curious views into people's homes, silly animated backgrounds when people barely had enough bandwidth for audio, we've suffered Zoom bombing by racist idiots, people who thought they were on mute but weren't, and people talking while muted, which is the new ALL-CAPS! We've had difficulty engaging students, who we have to coax to turn on their cameras and turn in their work. We have radically changed the way we taught this year, and all without much preparation. At times, it seemed a lot like this:

As vaccines are now available, allowing people to gradually return to pre-COVID ways of doing things, it will be interesting to see which aspects of this tech-infused approach to teaching we each decide to keep, and which will go back on the shelf. I’m sure that for many, who were thrust online reluctantly and without adequate time to prepare, Zoom fatigue and the lack of social interaction with colleagues will result in an eager return to old practices. Others may have found that the necessity created by the pandemic inspired a few new and innovative practices worth holding on to.

We proved that working online from home is effective, and that the flexibility it afforded had great value.

We reduced the use of gasoline so much that the price went negative and the skies over polluted cities cleared, revealing views of distant mountains many people had not seen in their lifetimes.

We made the realization that connection with our students and colleagues was still possible in the online environment, and we have stretched ourselves to learn new tools and teaching methodologies. We have made sacrifices to stay safe and well, but I feel grateful to all who have made difficult adjustments to keep the wheels turning. I hope we will continue to use some of the new tricks we’ve learned, and I also hope to see you all in person again soon.

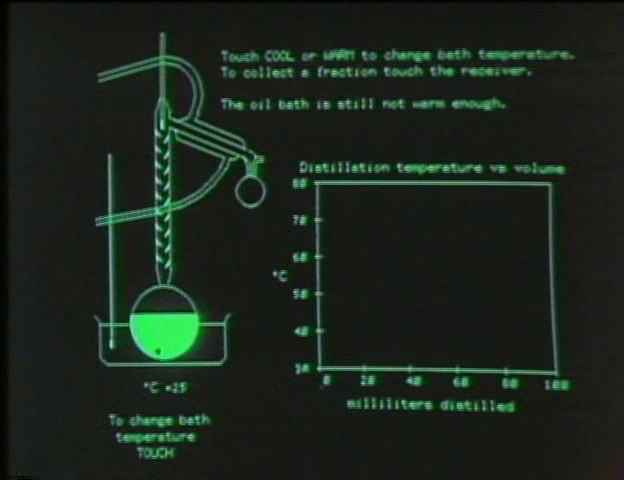

04.15.2019: The early history of Adaptive Courseware

Back in the beginning of what would become my career in educational technology, when I was a student teacher at Serrano Middle School in 1992, I had the rare opportunity to observe a teaching technology that would still be, or is again, considered cutting edge in 2019. The PLATO learning system, developed at the University of Illinois (the same computing powerhouse that brought us Mosaic, the first web browser) was being piloted in California and New York at a handful of public schools. It was an early version of what, today, we call adaptive courseware. PLATO was running on a genuine IBM server; a PC tower with a big toggle power switch near the top, that was networked to a group of thin client terminals set up in pods of four on round tables at the back of my mentor teacher's classroom. When I arrived, it was in use as kind of a drill and practice tool that occupied about a quarter of the students in the classroom at any given time. It was one of my duties to power up the system each day before the students arrived.

Over the course of my time there, I got a chance to observe the system and the way the students used it. Each student logged into the system individually, and was led through a series of multiple choice problems, often with a relevant graphic like the one above as a prompt. The questions were generally appropriate, relevant, and well worded. They were not the same for each student, and what I eventually gleaned was that they were presented dynamically, based on the students' answers to previous questions. If a student got a question right, the system would move on to the next topic or offer up a more challenging question in the same area, according to some algorithm. If the student got a question wrong, it would offer up an easier question, or more questions of a similar type. When the students completed a set number of questions, which was about 20 if I recall correctly, they were done for the day and the machine dismissed them back to the classroom and waited patiently for the next student. The classroom teacher had no part in this process, and was neither there to explain, nor encourage, nor guide the students. One thing my mentor teacher commented on with puzzlement was that some of his students, who were doing quite well in class overall, were doing so poorly on the computer that they were in danger of failing. I was asked to observe these students and figure out what was going on. What I found was that they were not reading the questions at all, nor attempting to answer them correctly. Often they would not even be looking at the screen. They would just hit the return key repeatedly to jump to the next question until they reached the required question count, and then rotated back into the regular classroom activities. Clearly, they were so unmotivated by this system that they were just trying to get through it as quickly as possible, and even the fear of a failing grade was not enough to make them try harder. Middle school students might be a particularly tough crowd.

What I learned that day, and what continues to be true today, despite higher resolution graphics and better animations, is that most students need an inspiring instructor to guide them, to praise them, and to motivate them to care about, and challenge them to understand, the material they are learning. This might seem astonishing to a computer programmer, who logically thought that students were there to learn and, if presented with clearly worded questions at the appropriate comprehension level, would rapidly progress to new levels of understanding. Evidently not. Most students just aren't motivated enough to learn entirely on their own. If they were, we wouldn't need teachers and schools, but only textbooks and libraries. When the computer praises them with a "good job" it feels empty. When it pushes them harder, they just lose interest. This might help to explain why MOOCs, a more recent attempt at competency based, self-paced learning, have also failed. The completion rate of MOOCs, according to a recent and ongoing study, is somewhere between 5 and 15 percent.

Can this type of learning work? I think we can say one thing for sure. It's not only the quality of the content, but the motivation and self-discipline of the students that determines whether independent learning can work. Maybe graduate students would make a better audience than middle schoolers. But even there, I think people respond better to an inspiring instructor than to a rich piece of content. A short video might pique your interest but to stick with it requires some recognition that you're working hard to achieve something, and some regular injections of real enthusiasm help! I'm just not sure that's something the computer can provide. Good news for teachers and professors everywhere. You've got some job security for now.

04.04.2019: AI or IA?

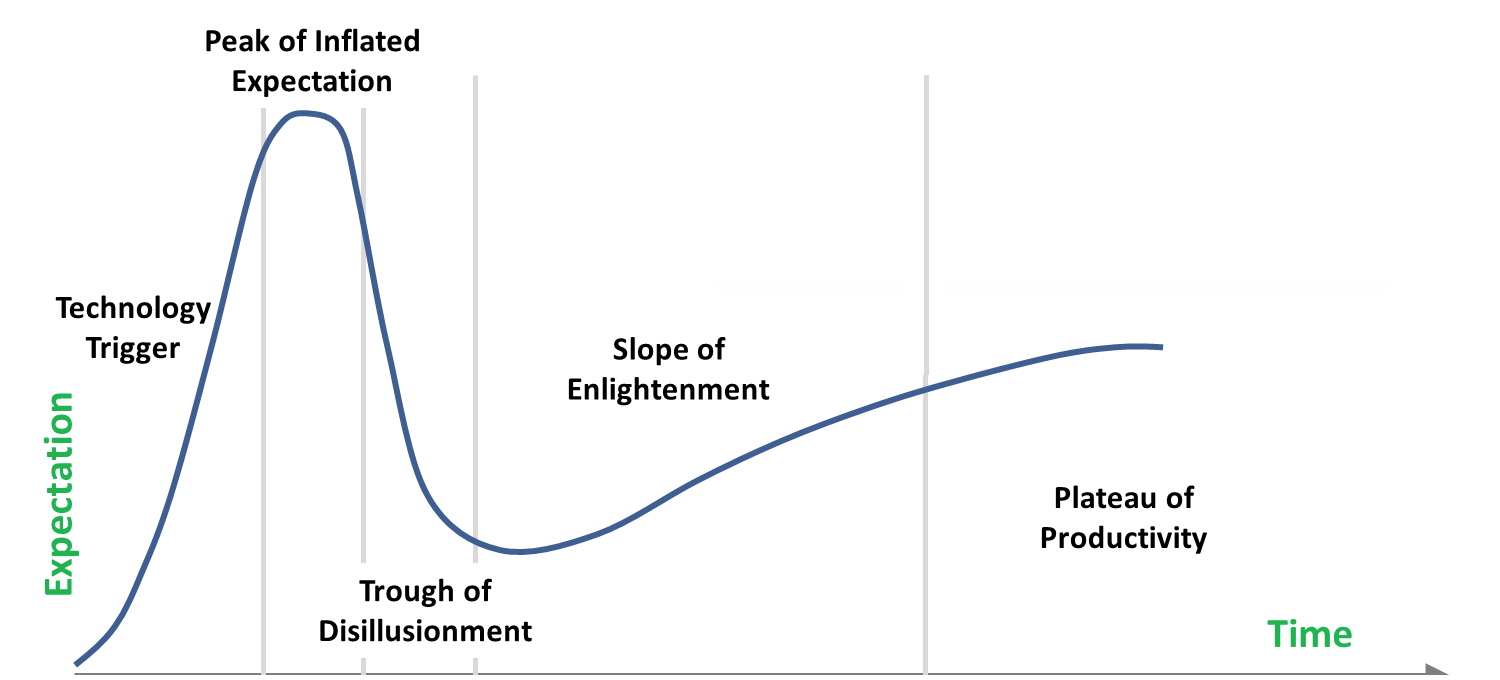

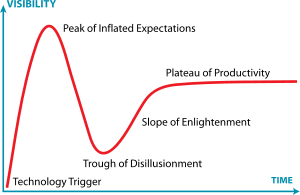

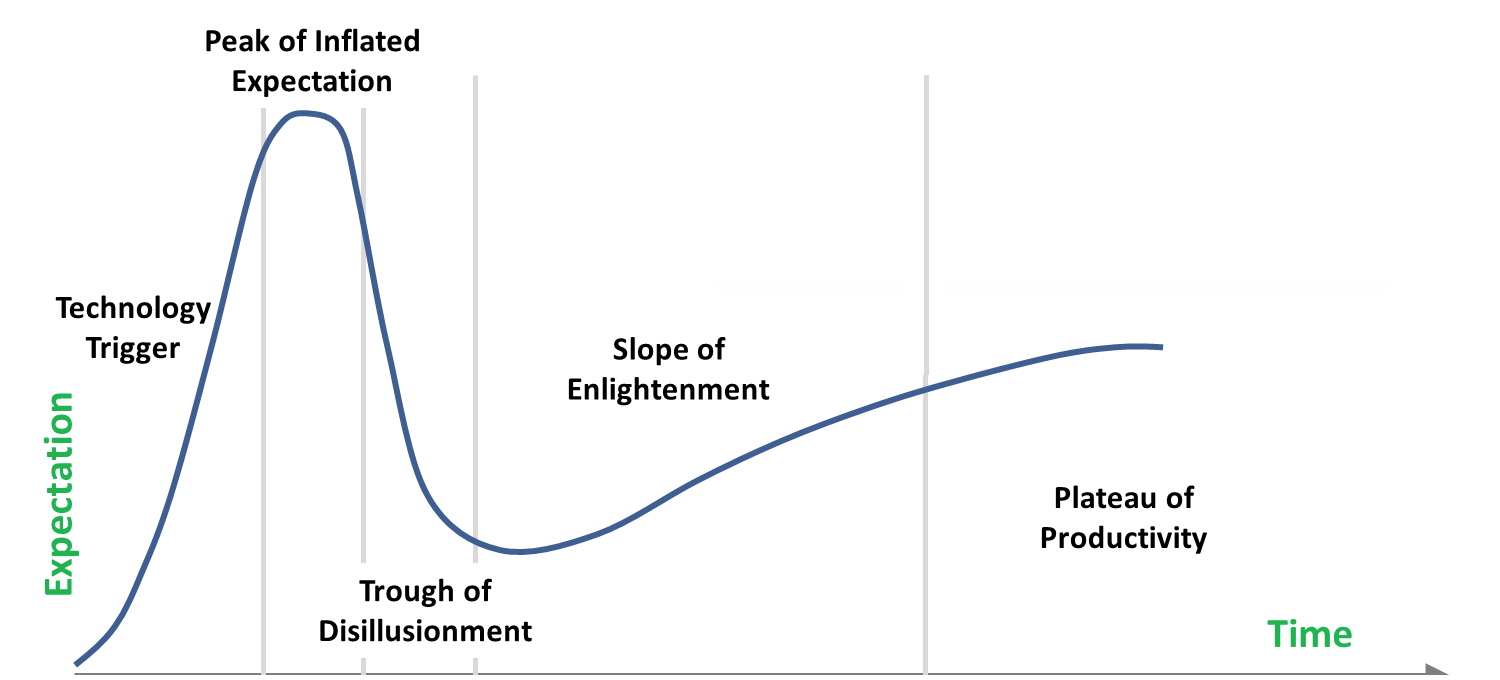

Artificial Intelligence is much in the news these days. On campus, we have six wheeled autonomous robots delivering food to the dorms. At an educational technology conference I recently attended, the inflated expectations around the potential of AI and "machine learning" were alarming; particularly so because I found myself in the small minority of skeptics. As I see it, there are several problems with AI. The first one is the biggest: it doesn't exist. What people are calling AI is just good programming. If a programmer can anticipate most of the common scenarios, it can appear as though the robot or program is intelligent. But it's not. My Nest thermostat has some clever programming. It lowers the temperature of the house when, using motion sensors, it determines that there's nobody home. Some people call this machine learning, but that's a stretch. This behavior was programmed by a person. The only thing that the thermostat "learns," if you can call it that, is our general pattern of occupancy. While that is cool and useful, true AI, as I see it, must be able to adapt to novel situations, to anticipate based on prior experience, and to avoid past mistakes. We are so far away from true AI that it's a disservice to use the term. Autonomous vehicles are a great example of programming based on anticpated problems. Equipped with GPS, an accurate digital map, and a collection of good sensors, a computer program can drive a car better than a distracted or drunk driver under most conditions, and maybe even better than an attentive novice driver when certain predictable conditions, like a slippery roadway, arise. But where it becomes clear that an AI is not as adaptable as a human being is underscored in the two recent tragic incidents with the Boeing 737 Max 8. If accounts are true, the pilots understood the problem perfectly, but were unable to wrestle control back from a misguided computer that, due to a faulty sensor, kept nosing the plane down to avoid what it "thought" was a stall, resulting in the deaths of almost 350 people. The best evidence that there was no intelligence in this AI is that both planes hit the ground at upwards of 600 mph, against the express wishes of the pilots. Some might argue that machine error is less common than pilot error, but that's a tough sell, and the machines are going to make different, dumber mistakes than the pilots would, at least in some situations. I hope we have learned from this example that an AI can't be trusted entirely, needs an easy to reach off switch, and that its judgment, especially when human lives are at stake, should be based on the input from more than one sensor. In fact, decisions should be based on the inputs from a minimum of three sensors, so that the majority rules when there's a disagreement. When someone steps in front of a food delivery robot, it freezes like a deer in the headlights. We can't afford to fly planes that way.

Rather than AI, I think what we need is IA. We need tools that allow us to visualize things we couldn't see in the raw data, to steady our hand, and to do things with more finesse than we could do unaided. What we need is Intelligence Augmentation, or IA, where there is a synergy between the real intelligence and the machine helper. The software that keeps a drone stable in a fixed position is far faster and more deft than a human pilot could be, but the AI will keep the drone in that hold position until it runs out of battery and crashes. In fact, a modern airplane relies on a variety of computers to assist in the flying of the plane. In the incident where Sully safely landed a passenger jet on the Hudson river after multiple bird strikes took out both engines, he deserves a ton of credit, but he brought the plane down on a glide path guided by the computer. I would rather live in a future where machines enhance or augment what we can use our intelligence and creativity and good judgment to do, rather than one where the machines lock us out and make the decisions on our behalf. When I first set up our Nest thermostat, I had miswired it so that the heat, once called for, never shut off. I woke up in the middle of the night to a house that had been heated to over 90 degrees and rising, and joked that the AI was trying to cook me. I can think of nothing more disturbing than being in the cockpit of an airplane, losing the battle with a machine intent on crashing the plane out of a misguided sense that it is being helpful. I have no interest in machines taking away our good jobs or our freedom of choice. I have never found Microsoft's Clippy to be particularly helpful at assisting me with making a numbered list. I believe in human potential, and technology that helps us to be more than we are; not less than we are.

02.12.2019: Disruptive Technology

The pace of technological change is accelerating, and many of these changes are disruptive to the kinds of jobs we do, and the kinds of services we enjoy. Consider how each of the following professions or industries has been disrupted:

| Old Industry |

Disruptor |

| Typesetting |

Desktop Publishing |

| Secretaries |

Word Processors |

| Bank Tellers |

ATM Machines |

| Music Industry |

Napster-->iTunes-->Spotify |

| Hotels |

AirBnB/VRBO |

| Travel Agents |

Expedia, etc. |

| Encyclopedias |

Wikipedia |

| News Media |

Social Media |

| Classified Ads |

Craigslist |

| Big Box Stores (Sears) |

Amazon |

| Yellow Pages |

Google |

| Taxis |

Uber/Lyft |

| Movie Rentals (Blockbuster) |

Netflix |

| Land Line Phones |

Cell phones-->Smartphones |

| Gas Powered Cars |

Electrics/Self Driving Cars |

| Maps |

GPS/Voice Navigation |

| Fossil Fuels |

Wind/Solar |

| Assembly Lines |

Robots |

| Medicine |

Genomics (PCR, CRISPR) |

| Academia |

Online Courses |

Did I miss any big ones? e-mail me your additions and I'll update my list. Where I work, in higher education, change has been slower, and less transformative so far, but I think we're just at the beginning, and I think there are a number of critical factors that will drive this change and disrupt academia too. The first is cost. An undergraduate degree has never cost more, but at least in the past you could be assured of a long and prosperous career if you had one. But in today's economy, employers tell us that our graduates arrive unprepared for the kind of work they'll be doing. Many of them will never earn the kind of incomes necessary to pay off those giant student loan debts, and most cannot even count on a job that provides medical benefits when they get sick. Under this kind of pressure, something has got to give. Maybe it's already started? Enrollments are down 9% since 2011 and a number of elite schools have shut their doors or engaged in mergers. These trends are even more worrisome in parts of the country that are losing population, such as New England and the midwest. It could be that the value proposition of an undergrad degree is fading, and that students are choosing to forego the debt load that goes along with them. We'll be watching this trend closely in the coming years, and trying to find ways to stay relevant and affordable. Personalized Learning, Competency Based Education programs, and online courses in general are promising possibilities, but the quality and relevency of these programs will have to increase, and there will be more schools on the losing end rather than the winning end. The keys will be ease of use (convenience), quality and breadth of offerings, and price, and it will be difficult to win without strong differentiation from the rest of the market.

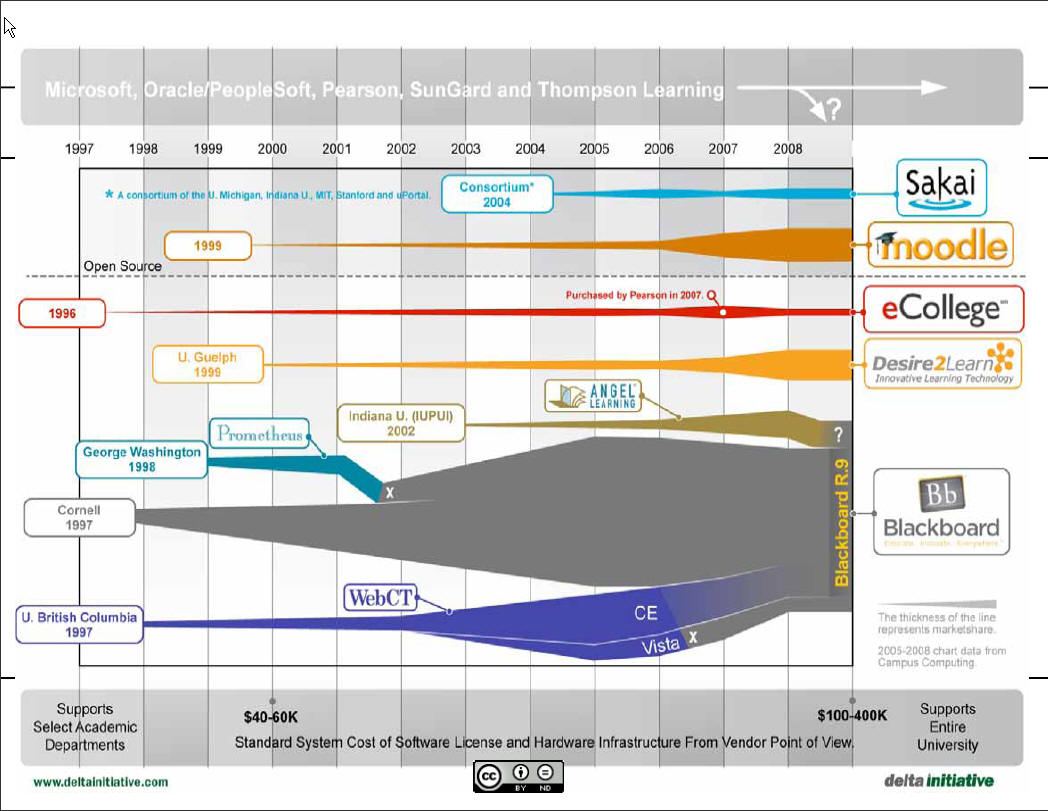

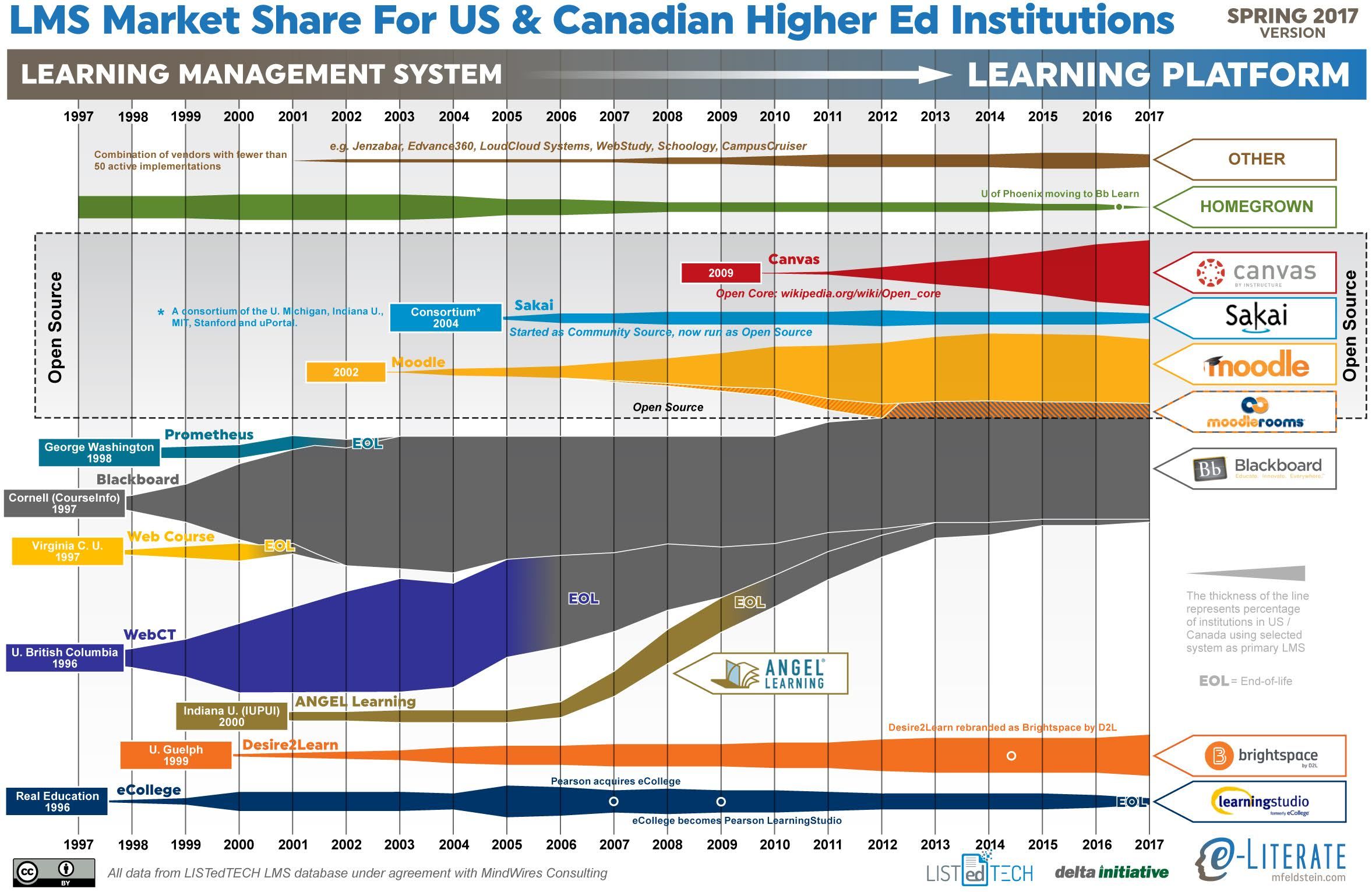

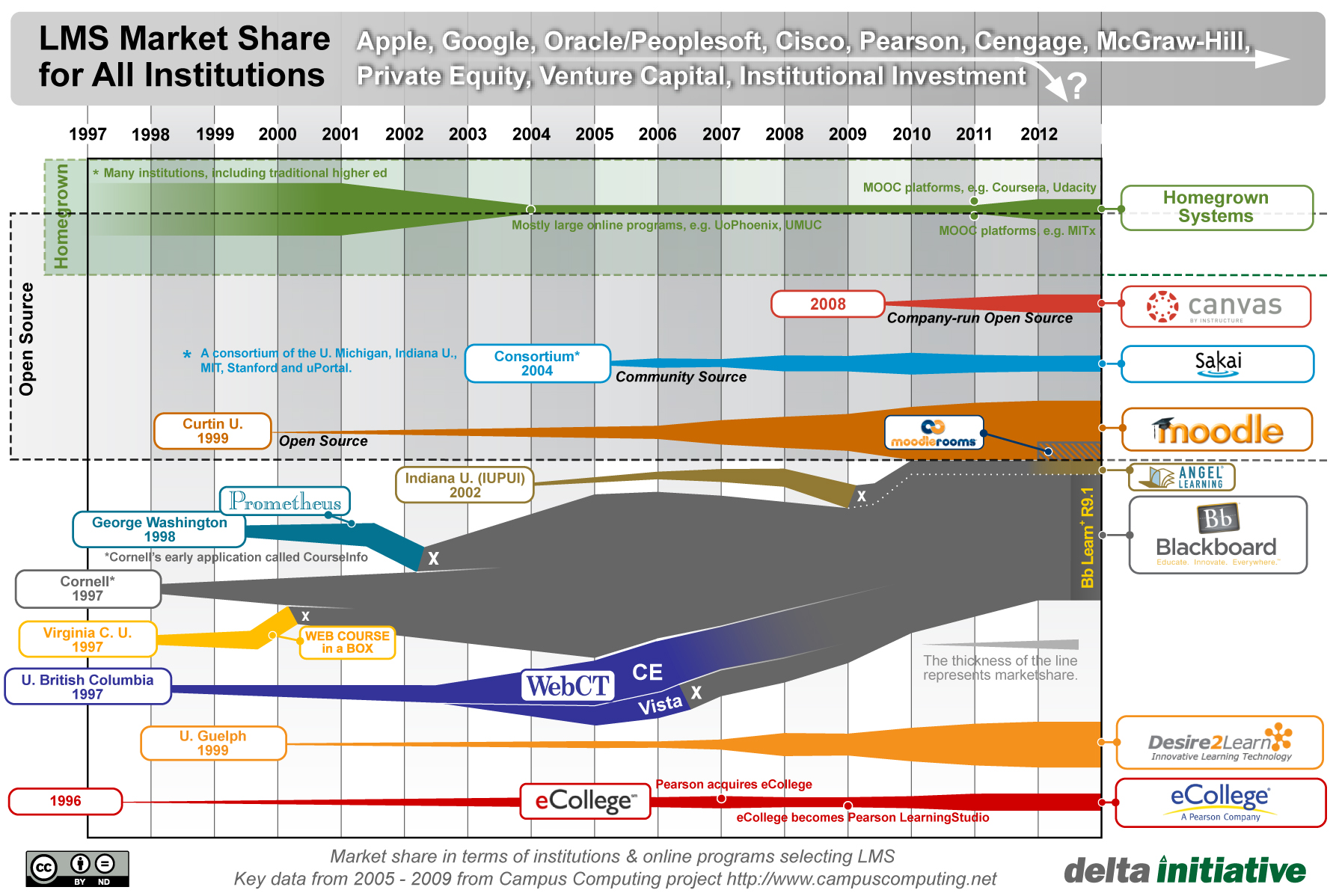

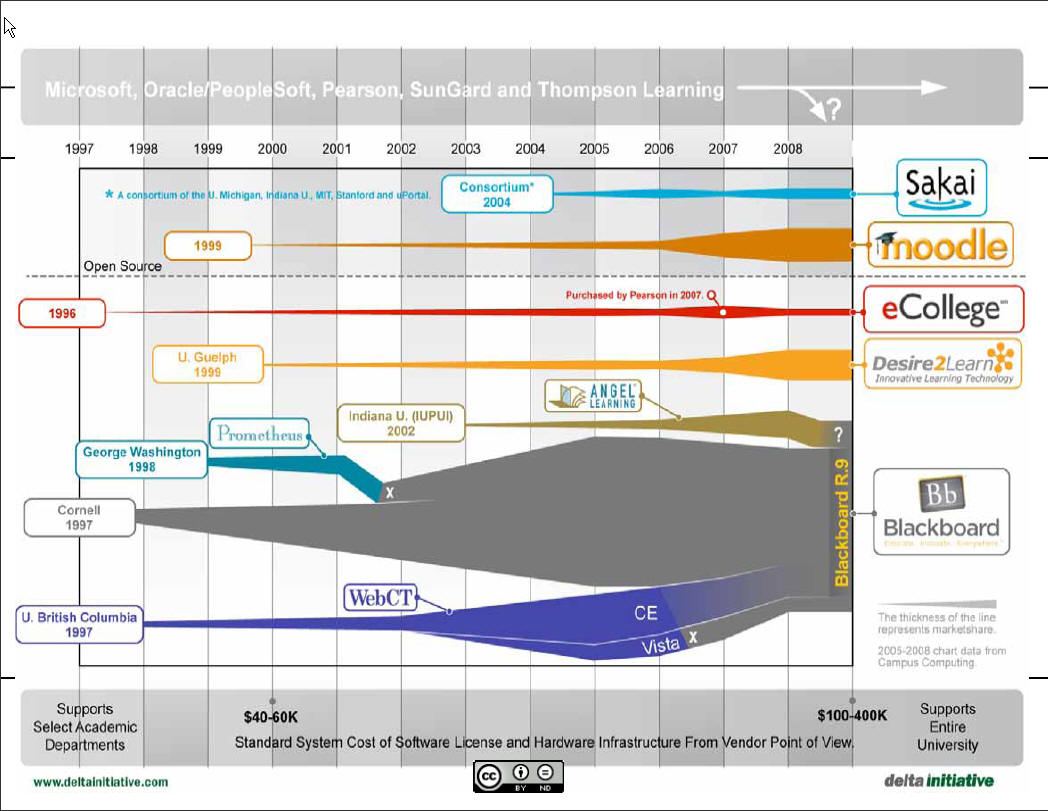

LMS Marketshare Latest Numbers

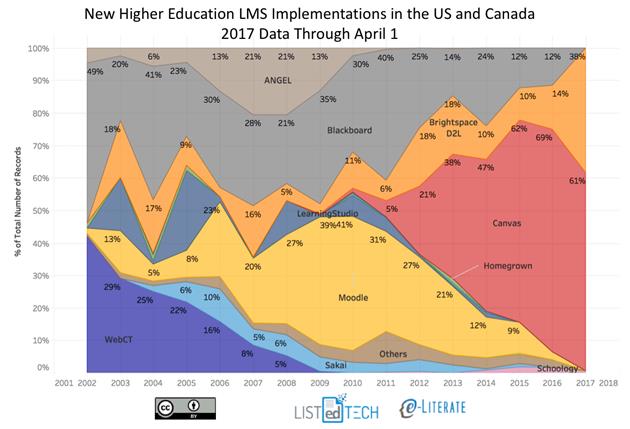

Blackboard has a big problem. Neither the absorption of major players like WebCT and Angel has helped them grow, nor has the dubious patenting of the LMS and the threat of lawsuits against competitors scared people away from the alternatives. Nobody is moving to Blackboard. They are several years into a complete LMS overhaul, and the migration path from Blackboard Learn to Ultra is anything but clear. It would be foolish for anyone to migrate to Learn at this point, because they will need to migrate again shortly, and it would be risky to commit to Ultra while it remains so unfinished, when there are solid alternatives like D2L Brightspace and Canvas to choose from. Blackboard desperately needs a win, and I suspect they made a screaming deal with the University of Phoenix, which has also struggled in recent years. The best Blackboard can hope for is that there won't be new defections, that current customers will move to Ultra when the time comes, and that Ultra will be good enough to attract new customers. That's a tall order.

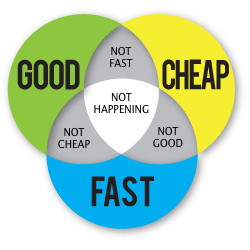

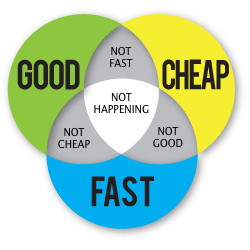

- Start small and build strategically (fast/cheap/good? pick 2)

- Identify some early wins!

- Evaluate and improve existing content with potential

- Create More Differentiation

- Who’s our competition?

- Community Colleges (cheaper)

- Other State Schools

- ASU (more students, more money)

- U of A (more prestigious, research oriented)

- For Profits

- U of Phoenix (in re-organization)

- Capella

- Strayer

- Southern New Hampshire University

- GCU (gained as U of Phoenix suffered losses)

- Western Governors University (accreditation issues)

- Arizona Regents University (now defunct?)

- This could be revisited so that students can more easily build a degree with a combination ASU, U of A and NAU course credits.

- What are their strengths?

- The For-Profits

- Great marketing

- A clear choice of offerings

- Organized, efficient, adaptable

- Well-funded

- The Public Institutions

- Cheaper

- In-person, blended, and fully online offerings

- Full-time faculty with deep expertise

- Reputation (trust of traditional institutions)

- What are their weaknesses?

- The For-Profits

- Credibility (skepticism about online degrees)

- Lower student success rates

- Higher costs; larger student loan burden

- The Public Institutions

- Disorganized, un-strategic online programs

- Faculty who aren’t experienced online instructors

- Reliance on “canned” content available elsewhere

- Resistance to, and slow pace of change

- How we can do better:

- Better Courses

- Existing Courses (but many need improvement!)

- We already have hundreds of courses

- We already have dozens of online programs

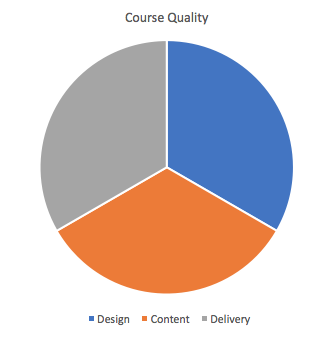

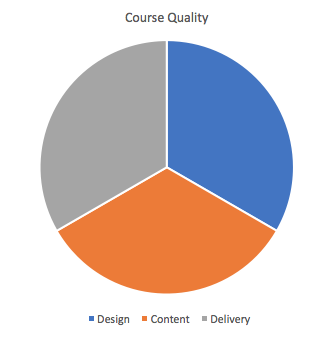

- Standards for Design, Content, Delivery

- Go Beyond QM: Cover All Three Elements of Quality

- Play on Regional Strengths

- Partnerships with Native American Colleges

- Partnerships with Community Colleges

- Tool alignment, resource sharing

- Take advantage of our geographical location

- Rural Arizona

- Native American Reservations

- Colorado Plateau

- Grand Canyon, Sedona

- Southwest

- Deserts

- Build Specialty Programs

- Be the Best at a Few Things, not bad at many

- Build gradually, strategically, intentionally

- Avoid expensive contracts with big publishers where possible

- Canned content creates a race to the bottom

- Use open courseware where possible

- Support strategic development of original custom content

- Develop select “flagship” courses available nowhere else

- Think Netflix and Amazon original content for example

- We already have a handful of unique world class courses

- No developing a course while teaching it

- Better Instructors

- Select for Online Teaching Experience

- Provide Subject Area Mentor Instructors

- Provide Training and Support in Online Pedagogy

- Waive in-state hiring requirement

- Required New Hire Orientation Training

- Recruit Faculty with TPaCK (Technology, Pedagogy, and Content Knowledge)

- Annual Peer Review of the course and the teaching

- Excellence Awards

- Incentives for larger (more profitable) classes

- Course development stipends (we used to pay $5000)

- TAs, Reader-Graders

- Adequate Compensation (stop the revolving door)

- Better Faculty Support (e-Learning has these skills)

- Experienced Pedagogy People

- Experienced Media Designers

- Established relationships with faculty

- Better Administration

- 3-6 month new course development process

- Course refresh and continuous improvement process

- Master course archive

- Better LMS and other tools

- Short term: Get PL onto Blackboard (now)

- Medium term: Integrate PL with adaptive courseware tools (1 year)

- Long term: Consider an LMS transition (2+ years)

- Faculty are ready to move, Canvas is the most popular option

- Better Credibility

- Keep ProctorU

- Keep Kaltura

- Adopt TurnItIn

- Build and Staff Testing Centers (this is controversial)

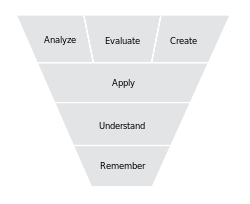

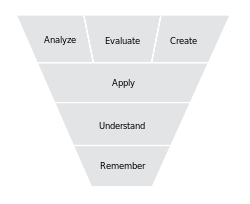

- Promote Higher Order Thinking Skills

- Allow collaboration

- Allow the open web

- Shift away from memorization

- Build the reputation (this will take time)

- We need to stick with it for at least 5 years!

- We need to market ourselves like the non-profits

- We need to improve the clarity of our offerings

- Lower Operating Costs

- Open Source Materials

- Retention of Talent

- Efficiency

- Clear Focus

- Better Student Support

- Assistance with Financial Aid

- Assistance with Course and Program Selection

- Monitoring of Student Progress

- Better use of Analytics

- Timely Intervention

- Don’t worry about local students taking hybrid and online courses

- Students will do what works for them

- Flexibility

- Personalized Learning

- Variable Course length

- Variable Start times, End Times

- Mastery is what matters most

- Great Self-Service Options

- Personal Attention

In a meta-analysis of a dozen recent studies, a non-profit education research organization has concluded that there is

no significant difference in student learning outcomes when comparing performance in face-to-face courses with hybrid and fully-online courses. Mode of delivery matters less than the quality of the individual course and its instructor. No surprise to me! This finding backs earlier work.

http://nosignificantdifference.org

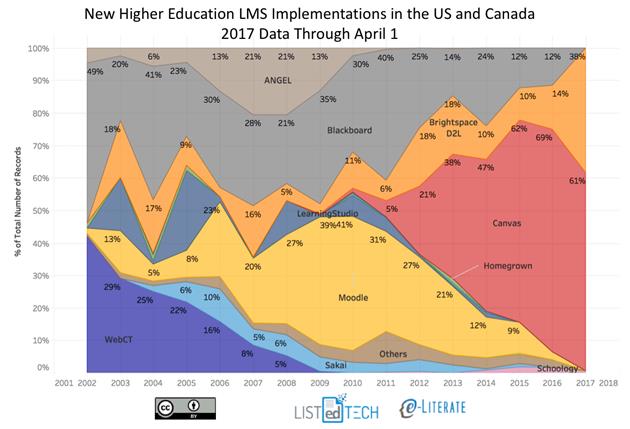

If you're changing LMS this year, you're likely going to Canvas

If you're changing LMS this year, you're likely going to Canvas

Although the title of the e-Literate article says that Blackboard may be turning things around, the graph doesn't show it. If you're a school in the U.S. or Canada and you're changing LMS, odds are high that you're going to Canvas (61%) or D2L Brightspace (38%). Note that this graph does not represent current market share, but where the switchers are going. Still, it's a strong predictor of future market share, and it shows that Blackboard's in trouble. Blackboard's current goal seems to be to hold onto existing customers and stop the bleeding until their next-gen LMS, Ultra, is ready for prime time. That date has been slipping for some time however, and I'm pretty certain that if I had to switch LMSes today, I'd go to Canvas. I've been a fan since 2009. But the decision to switch is not an easy one. Changing LMSes is like moving to a new home in a new city in a different country. It's not to be undertaken lightly, because the move is difficult, time consuming, costly, and painful, even when the end result is a better system. So why isn't anyone moving to Blackboard? The answer is simple. You'd have to migrate twice. Once to the current system, and then to the new one. That would be nuts.

In case you missed it, Western Governors University has been audited by the Federal Department of Education and found not to be distinctly different from a correspondence school. If the finding is upheld, WGU could be forced to return $713 million in federal financial aid. This has serious implications for all schools involved in distance learning and personalized learning! But the Feds are right about one thing. An online course can and should be much more than a correspondence class.

10.13.2017 Update: "WGU is not off the hook."

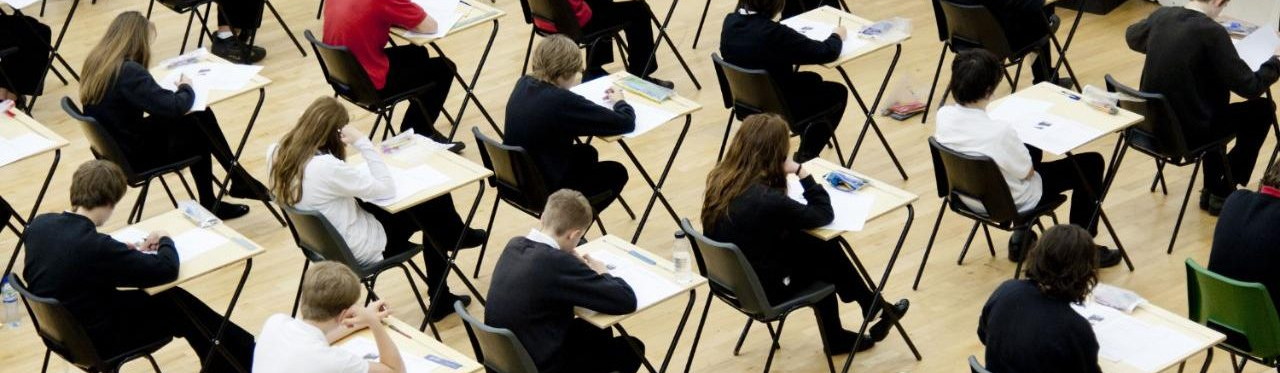

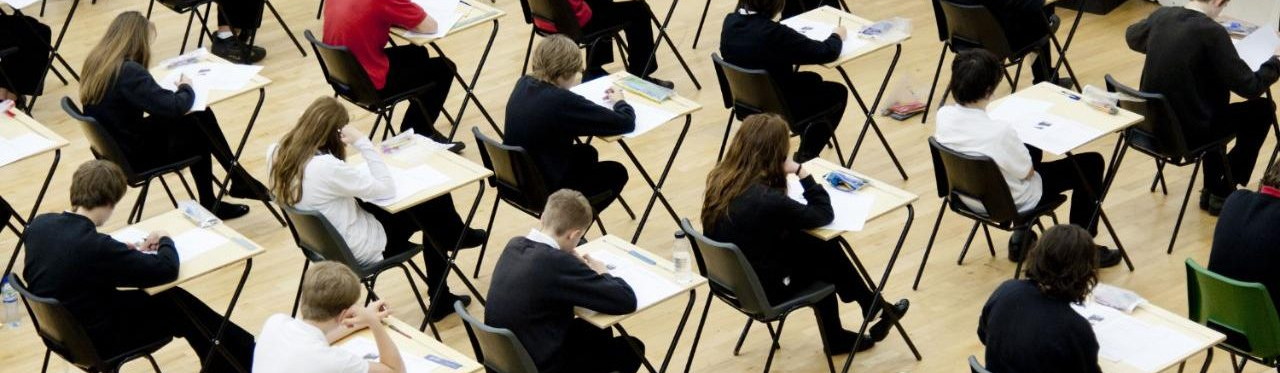

Traditional testing forces students to cram, regurgitate, and forget.

Traditional testing forces students to cram, regurgitate, and forget.

Have you ever thought about why we test students the way we do? What do I mean? Well, we generally test students in isolation from each other. We generally disallow aids like notes, calculators, textbooks, cellphones. We ban the use of Google and Wikipedia. We set strict time limits and restrict you to your seat. We use a lot of multiple choice and fill-in-the-blank, with perhaps a smattering of short essay. Someone is watching you constantly. Now, you may be thinking, "Of course. How else can we keep them from cheating? How else can we find out what they know? How else can we keep them from helping each other?" I would argue that those are the wrong questions. Sugata Mitra has an interesting TED talk, where he develops the idea that the present day education system remains much as it was designed by the British empire in the 18th century. At that time, what was needed were clerks and bookkeepers who could do math in their heads, and read and write without need of help, primarily to keep track of goods moved around the world in sailing ships. He argues convincingly that the education system isn't broken. It works remarkably well. It's just that it trains students to do things that there is little need for in the information age. Rather than testing for the ability to memorize and regurgitate without understanding, we need to redesign assessment around collaboration, persistence, synthesis, and creativity.

When we attempt to solve a problem at home or at work, what are the first things we do? Gather some background information. Consult an expert. Get some help. Brainstorm. Try more than one approach. Keep at it. None of these methods are allowed during a test, but this is the way we solve problems in the real world. Sure, we need to have the vocabulary. When I go to the hardware store, I need to be able to explain the problem so they can recommend the right tool. Yes, I need some basic understanding as a foundation. But why, in the 21st century, when all of the knowledge of humanity is a few clicks away, must I regurgitate memorized facts on an exam without any help? How often would I not have access to these resources in the real, everyday world? Perhaps if I'm lost in the woods, and my cell phone is out of juice, then I would need to solve a problem in isolation and without assistance. But that seems more like the exception than the rule. Cramming for a test, regurgitating a collection of memorized facts, and forgetting it all the next day is like being a bulimic. There is little educational value in consuming information that you can't retain, just as there is little nutritional value in eating food you don't keep down.

Most problems we face in the real world don't occur in an isolation chamber. They don't have someone hovering over you with a stopwatch. They don't require that all of the knowledge required to solve the problem is already in your head. They don't require you to stay seated, or to work alone. They don't present you with five distinct choices, only one of which is correct. They don't allow you only one attempt. That would be crazy. And yet, that's exactly how we test students, from elementary school all the way through college. Think about these questions for a bit. What kinds of students are successful at that kind of testing? How well does that reflect their future performance on the job? What skills do employers regularly ask for? When hiring someone, is it more important that they already know how to do the job, or that they are creative, persistent, able to learn, and able to work well with others? How well do we prepare students for the challeges they will face?

What are the skills we need to employ in modern day problem solving? Usually, they involve gaining an understanding of the problem, either by doing research or getting help from someone who knows more about the topic. Once we understand the problem, we develop one or more strategies to solve it, based on cost, time, effort, available resources. Often, the first solution is inelegant, but it might be good enough. "Fail small, fail often." is advice I've heard from many successful problem solvers. Don't be afraid to try things. Break the problem into pieces and solve each part separately. Creative solutions rarely come from aiming directly at the problem and going full speed ahead. But the key point here is that we learn to be creative by attacking problems not with a head full of facts, but a kit full of tools that can be used again and again. You may be thinking that I've got a point, but it's easier to grade answers right or wrong when we test facts, not opinions. However, it's actually not so hard to grade students a better way. You look at how they tackled the problem. It's the difference between awarding points only for the answer versus asking students to show their work and evaluating both the quality of the end product and the sophistication of their methods. Let them work in teams. Let them use any resources they can get their hands on. This is an approach to teaching and learning that actually prepares students for a job in the real world.

"But wait," you're saying. "If I assign group work, how can I tell who did what?" Yes, that can be tricky. We've all been assigned to a team where one person does almost nothing, and gets the same amount of credit as those who pulled most of the weight. That's a problem with the way the group members were evaluated. But guess who knows who did which parts of the job, and how well they did them? The members of the group. A very clever way to grade students is to have them evaluate their own performance and that of their fellow group members by secret ballot. Average out the peer grades and compare it to the grade they gave themselves. You'd be surprised how accurately this will match your own observations, and how well it reveals who did the work. Of course, you also assign the work an overall grade, so that if everyone agrees to give themselves higher grades than they deserve, there is a correction factor. This method may need to be employed more than once before students realize that their actions are accountable, so don't give up after just one try. You will find that it becomes even more effective as time goes on.

There is another thing you can try when assigning group work, if you're still having challenges. Identify the different kinds of work necessary to put together the final project. For example, in a lab experiment, one person is the group manager, whose job is to lead, organize, plan, make decisions and settle disputes. Another is the experimenter, the hands-on person, who must be good at understanding and following instructions. A third is the data collector, who might also be in charge of creating graphs and charts. A fourth is the analyst and writer of the report. A fifth is the presenter. These are somewhat arbitrary divisions of responsibility, but you get the idea. When you assign duties within the group, people sort themselves into the kind of work they like to do. Students who hate to get up in front of others and talk might be excellent writers. Students who like to present might not want to get their hands dirty, or be good at following detailed instructions. That's ok. Everybody can make a contribution. And, if someone really wants to work alone, let them. As long as they understand they have to do the same amount of work as a whole group would, that's fine. That's how the world works.

Panel discussion on 21st Century Classrooms

Panel discussion on 21st Century Classrooms

Recently, I was asked to speak about what I envisioned as the "classroom of the 21st century." Given that we're already 15 years into the new century, that might seem like an easy task. However, when asked to predict the future, I always think of the scene in the movie "Metropolis" where the bi-planes are flying between the skyscrapers. Or in 2001: A Space Odyssey, where the spaceplane is owned by the now defunct Pan Am Airlines. The future tends to unfold in ways we can't imagine. Some of the (at the time) amazing technologies of Star Trek, like the communicator, already look primitive compared to today's devices. Others remain as far away as another star system.

This venue was at a technology conference sponsored by technology vendors, so the expectation was that we would talk about technologies that would transform education as we know it. There were impressive demonstrations of virtual and augmented reality, and telepresence; things that require lots of bandwidth, robust connections, serious computing power and, most of all, a lot of back-end technical support. One of the presenters showcased an elementary school in Ireland that was doing cutting edge stuff with VR, but noted with incredulity that, in one of the slides, the child was sitting in front of a CRT monitor rather than a flatscreen. Another presenter lamented that one of the challenges in K-12 is that the computers found in public schools don't often have video cards capable of keeping up with his 4K video. Unwittingly, these presenters got to the heart of the problem. Public schools, even in the 21st century, don't throw away old equipment that still works. A cathode ray tube monitor may be a throwback to the 1990s but, if it's working, it will continue to be used and limited funds will be diverted to higher priorities, like things that don't work at all. In my experience, schools don't even throw away broken stuff because they may need to cannibalize it for parts. Teachers are resourceful and frugal.

Now if you've read any of my previous blogs, you already know that while I like technology, I am often skeptical about expensive technical solutions to pedagogical problems. I recall when I taught high school in southern California, one of the teachers, a friend of mine, worked in a south facing classroom with a big bank of windows, and actually passed out in front of her students one sunny spring day while teaching in the 90+ degree heat. The administration had a priority system, however, for installing air conditioners. If the room had a computer, it could have an air conditioner because the administrators didn't want the computers getting damaged by operating in excessively warm conditions. At my urging, she requested a computer, for which there were ample technology funds, and she got an air conditioner as part of the bargain. I don't think she used the computer at all, but she let the kids who finished the lesson early play solitaire as a reward. And she effectively delivered her lessons in a classroom that was at a pleasant 70-something degrees. That's the kind of creative thinking it takes to operate in the 21st century classroom.

iPads are a recent example of a technology that was supposed to transform education. Large school districts made multi-million dollar deals with Apple to put an iPad in the hands of every student. They were supposed to replace textbooks. They were supposed to fill students with wondor and the passion to learn. That didn't work. A few years down the road, many of these districts are finding that iPad management tools are lousy, the devices are fragile, and they go obsolete far too fast for the money they cost. But the biggest problem of all might be that many students already have one at home and use it primarily for playing games, so that's what they want to do with it at school. Many districts are now dropping iPads and looking at cheaper, more rugged Chromebooks. While these may prove to be a better investment, the top-down approach to deploying technology remains a problem.

Top-down technology investments in education assume that if you make a technology available, the teachers, who are dedicated professionals, will figure out some appropriate instructional uses. This is the wrong approach. We need to design curriculum with the learning objectives in mind at the beginning, and then provide the necessary instructional support resources, including but not limited to technology, to help make the learning happen. That means we need to ask teachers what they need and, where reasonable, do what we can to meet those needs. Some teachers might make great use of iPads, while others would prefer video cameras, or art supplies, or new textbooks. When the teachers at my school were asked to help design a new science building, they asked for lab benches at the back of the classrooms, including big flat work surfaces, with clean sight lines, and lots of storage cabinets. The need was easily met, and the rooms were both popular and effective. However, the architect decided to ignore their request for windows, so the biology classrooms can't have any live plants. A classroom designed around the needs of the individual teachers and the learners is going to be far more effective than a top down directive to use this or that gadget to transform the learning process.

Sometimes a technology is offered as a solution to a problem because of cost or practicality. One example I heard recently was that field trips and labs are too expensive, so let's "virtualize" those experiences and then the students can learn about the Grand Canyon, or a marine ecosystem, or the anatomy of the frog on the computer. The result is never as good. Intuitively we all know this, and yet we are lured by the promise that it will be just as (almost as?) good, and will cost less, or be safer, or will not require tedious permission slips, etc. But the experience isn't the same. The canned tour of the canyon doesn't include a tough hike. It doesn't smell like hot dry air and desert flowers. It isn't nearly as fun. I can't flip over a rock in the simulation, because the designer didn't program that option. The slippery boulders, the icy cold water, and the experience of catching a fish out of a tide pool with a dip net are so much more vivid than the best sim. And it turns out that the infrastructure and technology required to design, deliver, and support a really good virtual reality experience is incredibly expensive. Perhaps more expensive per student than a dozen field trips. A cadaver lab is very expensive, but I want my medical students looking at real specimens rather than photos and canned simulations. How else can they discover individual variability? Or the effects of aging or disease? Or differences between male and female. When a doctor goes into surgery, you don't want to hear the words, "It didn't look anything like this in the simulation." Even if it costs more, the experience is worth the price if the students remember it years later, and that's much more likely with the real thing than with a simulation.

So what does a classroom of the 21st century look like? I have two kids, ages 10 and 13, in the school system right now, so I can tell you. Generally, it's a poorly designed, overcrowded room in a decades old building in need of major maintenance, with peeling paint, lousy acoustics, a heater that clanks all day long under flickering fluorescent lights, a mix of brand new and ancient, working and broken equipment, a lot of duct tape and plastic buckets, and a whole lot of heart. The passion and drive of dedicated teachers is what keeps it all going. Ok, so that's what we've got. In my dreams, what could we have?

The top priority is support. Give teachers the support they ask for. Did you know that teachers supply most of the classroom materials they need out of pocket, and rarely get reimbursed? Putting an expensive technology that nobody asked for into a classroom is not going to be effective. Raising salaries, reducing class sizes, or providing funds for a teacher's aide, or fixing the broken desks and chairs is generally what teachers are looking for. If they want to use a technology, by all means, see if it can be provided. But ask them what they need rather than tell them what they should be doing. That alone would revolutionize teaching and learning in any century.

Even if the teachers wanted a specific technology, and got it, the support for it tends to end when the technology has been set up by a technician. How many bad PowerPoint presentations have you seen? Was PowerPoint broken? Nope. It was misused. Without the kind of tech support and professional development needed to ensure that the technology is used properly, these high-tech initiatives always fail. There are some great and effective uses for technology that can facilitate teaching and learning, but the initial investment must be followed up with funds for ongoing maintenance, tech support, training, and planning.

Some people imagine a future where students are taught entirely by computers with clever algorithms that adjust the content to the pace of the learner. In my mind, this is like getting your nutrition from a pill. In the near future, I don't see a computer, no matter how cleverly programmed, inspiring students the way a good teacher can. If we invest in teachers, and let them pick the technologies they want to use, the classroom of the 21st century could really knock our socks off! It might not be cheap but, as the joke goes, "Education might seem expensive, until you consider the alternative."

photo credit: collegecandy.com

photo credit: collegecandy.com

Michael Wesch is one of education's big thinkers. One of his notable sayings is that "College is for learning, and everyone can learn, so college is for everyone." That's a lovely sentiment. On the surface, it seems so obvious that it's like a human right. It should be in the constitution. Life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness, and a college education. Some have even gone so far as to say that a college education is such a fundamental right that it should be free for everyone, paid for with tax dollars! But as great it would be for everyone to be smarter, and as nice sounding as Wesch's syllogism may be, he couldn't be more wrong. The transitive property works in math class, but his logic is deeply flawed. College is not for everyone.

It's September, and I work on a college campus, and I see so many smiling, happy students walking around, riding their skateboards, playing with their smartphones, rushing for fraternities and sororities, drinking their $5 coffees in their exercise wear. And I think to myself, "Why are you here?" I have heard all of the answers many times. Senior faculty say, "you're here to learn how to think." Junior faculty say, "You're here to learn about this subject." Serious students say, "I'm here because I want this or that career and, to get there, I need this or that degree." Less serious students say, "Well, I graduated from high school, and college sounds like a good party." Parents say, "A college degree helps you get ahead." The Administration says, "We offer a number of excellent programs, and if you are admitted, (assuming you pay, and you work hard) you can get a degree in this or that." All of these statements are mostly true. And yet, college is not for everyone.

A person can learn a lot without spending any money on a college degree. Wikipedia contains all of the information I studied in college. Before the Internet, all of that information was also in the public library. What colleges provide, for a price, is a certificate that says you have progressed successfully through a course of study. The degree is to knowledge as money is to gold. The degree and the dollar are only pieces of paper that represent something of intrinsic value. The employer accepts the value of the diploma. But what happens if a nation just starts printing its currency without the resources to back it? What happens if colleges start cranking out diplomas for everyone who shows up with a student loan? And even if we don't allow that standards have slipped (though it seems likely they have, since there is not an unlimited supply of deep thinking, hard working students, and the number of qualified, full-time faculty is actually in decline at most institutions) if there are more people with diplomas and the number of jobs remains constant, the problem of supply and demand takes effect. The supply of diplomas outstrips the demand of employers. It becomes a buyers' market, and the value of your degree slides.

I would argue that a college education can be a great and wonderful thing if one takes it seriously. But the growth in enrollment, and the growth in cost, to me, looks an awful lot like the recent housing bubble. I just watched an excellent movie called "The Big Short" and one of the points it made is that housing prices kept rising through the nineteen-eighties and nineties, and houses kept selling, even while incomes remained flat. How was that possible? It was possible only because people were getting loans for houses they couldn't afford. Today, there are an awful lot of people taking out big loans for college degrees and those degrees, in many cases, are not leading to good paying jobs. Doesn't that sound like a bubble?

So why isn't college for everyone? Because as more and more people go to college, the value of the degree is diminished. Most employers look for a degree but don't pay much attention to the school you got it from, or the grades you got. Therefore, with the exception of a few elite schools, all degrees are equivalent. Most people today don't end up working in a field related to what they studied in college. Most employers are looking for things you didn't learn in college. As the diploma is devalued, employers will need to use other criteria to decide who to hire. That's already happening. Everyone who applies for a job has a degree. It remains a prerequisite. But for how long? How long before employers start saying, "anyone can get a degree, so we don't care whether or not you have one." And if the degree stops giving people an advantage, it won't be long before people stop paying for it. At some point, doesn't it seem likely that this bubble will pop?

If you're not serious about your studies (and, honestly, how many kids fresh out of high school are?) chances are pretty good that your grades are going to suffer. After all, you have shelter, money, food, you're surrounded by people your own age, and you're out from under mom and dad's rules. Party on, right? That's not to say that college is only about academics, but it should be at least one of the reasons you're there. A gap year or two, working a job, might be a very valuable experience, even if it's not, and maybe especially if it's not, the greatest job. There are lots of things to learn outside class. Learning how to live on your own, cook and clean for yourself, and figure out who you want to be are all important. But you don't necessarily need to be in college, at least not right after high school, in order to do those things. Learning how to show up on time, get things done, deal with bad customers, bad bosses, bad colleagues, bad roommates, live within your means, and pay your bills are all very valuable life experiences we don't learn in high school or while living at home. So why not save some money, think about what you want to do with your life, grow up a little, and bide your time? And if you decide college is not for you, there are lots of careers where you can do just fine without a college degree. In Germany, for example, only about the top 30% of high school students go to college. Many more go to two year trade schools or apprenticeships and get jobs in areas where a four-year degree is not necessary, such as factory worker, physician's assistant, plumber, technician, carpenter, bank clerk, etc. When they change jobs, they may require more training, but the 4-year general degree isn't useful.

College isn't for everyone. Yes, everyone should have the opportunity to go, if and when they are ready. But you need to know what you want to do with your life, be open to new ideas that will make you rethink what you thought you knew, be passionate about learning for its own sake, and be ready to work harder, study harder, write better, and think deeper than you've ever thought before. College recruitment ads should be like those drug commercials:

"College is not for everyone. Known side effects include crippling debt, confusion, exhaustion, disillusionment, joblessness, and depression. Consult your professor to see if college is right for you."

By the way, just in case you don't want to take my word for it, the guy who made billions shorting mortgages when nobody else thought there was a housing bubble is now shorting the for-profit colleges.

The Good:

NAU has received a grant from APLU (the Association of Public Land grant Universities) to explore Adaptive Courseware with our faculty and students. Before we get into the details, it's a good idea to unpack those words. Courseware is content in software form, rather than a physical, bound, paper textbook. It's also a collection of assessments (tests) of the learner in various machine gradeable (multiple choice and similar) forms. But e-books from the big publishers like Pearson, Wiley, McGraw-Hill, and Cengage have been around for a while and are in fairly general use. It's the adaptive part that's new. Both the course content and the assessments can be adaptive.

So what do we mean by adaptive? The basic idea makes great sense. The idea is that the software monitors the way the students progress through the course material, and how they do on the assessments, records their responses and their path for analytic purposes (noting parts of the course that are causing problems for students, for whatever reason) and presents different content and test questions based on their responses. This makes perfect sense. If a student isn't getting it, or if they are bored silly, it makes no sense to keep throwing more of the same stuff at them. It makes much more sense to divert the struggling student into remedial or preparatory content, and to present deeper, more sophisticated content to the student who isn't being challenged.

What are the reasons students have problems with the content? The three most obvious ones are that 1) the content is unclear, 2) the content is not engaging, or 3) the content is not appropriate to the student's level of prior knowledge. With data, we can fix these things and make the course better, with the ultimate goal of aiding the learner.

Why is this, potentially, a great idea? Retention of students is better than losing them and recruiting new ones. Making sure that students are ready for the courses they are enrolled in increases student success in a meaningful way, makes professors happier, and ensures that the reputation of the institution improves.

How does this transform education? As content is personalized, it breaks the traditional lock-step approach, where (if we're lucky) the middle 50% are getting it, the bottom 25% are failing, and the top 25% are bored. It allows struggling students to get the background information they need to succeed, and it allows the advanced student to finish early or go farther, and to have that deeper level of mastery get recognized. It allows everyone to proceed at their own pace, and to spend as much time as they need on the parts that are challenging, and to go deeper into material that interests them.

Well, that all sounds great. What's the catch? That's next...

The Bad:

For our first round of product reviews, we're looking at four vendors: Acrobatiq, Knewton, Cogbooks, and Learning Objects Difference Engine (a division of Cengage). What we have quickly realized is that each of these tools has a very different user interface, which goes against the efforts we've been making to create a more consistent look and feel across all NAU courses. This makes it more difficult for students to navigate because every course might be very different in its layout and design. It also relegates our learning management system, Blackboard, to the role of a portal. Students log into Blackboard, find the course, click on a link, and then leave the LMS and land on one of many possible courseware sites. With lots of integration work, we can get grades back into the LMS, but that's about it. Nothing lives in the LMS.

We have also realized that adopting these tools results in a considerable loss of intellectual freedom over content and delivery of a course, because the content is deeply intertwined with the adaptive engine. In order to get good analytic data on learner behavior, content needs to be thoughtfully tagged, and progress needs to be carefully tracked, and this makes authoring content more challenging than just knowing the subject matter. In most cases, authoring is a job for professionals, not content experts. From the vendor presentations, it's not clear what the role of the instructor is with these tools, and therefore it's hard to see where our faculty experts can add value or personalize the content.

Difficulty customizing content raises another question. How does one school differentiate itself from another if they are both using the same product, and the product is not very customizable? How does NAU compete against a school with lower tuition costs, for example? How does an NAU instructor integrate content on life at elevation to a Biology course; something that is both relevant and interesting when you live at 7000 ft? When students can shop around for courses, why would they pick our version?

Another common objection is that students who don't get it have more work to do, or that students who are doing well get more work piled on. This may seem reasonable, but it is a very foreign concept for most students, and the students will resist it unless the rewards are tangible. We haven't transformed the rest of the educational process, so those rewards are not clear at present.

The final issue is that, beyond the introductory level, there isn't (and may never be) a lot of adaptive courseware content, because it's a niche market. There is also not, at present, much content that isn't machine gradeable. That means that liberal studies and the humanities are not going to be well-served in the near term. Therefore, this is not a complete solution.

The Ugly:

The APLU grant is only seed money. Purchasing adaptive courseware is a new financial burden that will fall either on students or universities. It's pretty clear that this is the future and, if they get it right, the potential is great. But it's also clear that we're moving towards a world where people are taught by machines, and the human factor is being pushed to the side. Are we doing this because it's a better way, or because it reduces costs? I don't know about you, but a computer telling me, "Great Job, Larry" isn't very motivating.

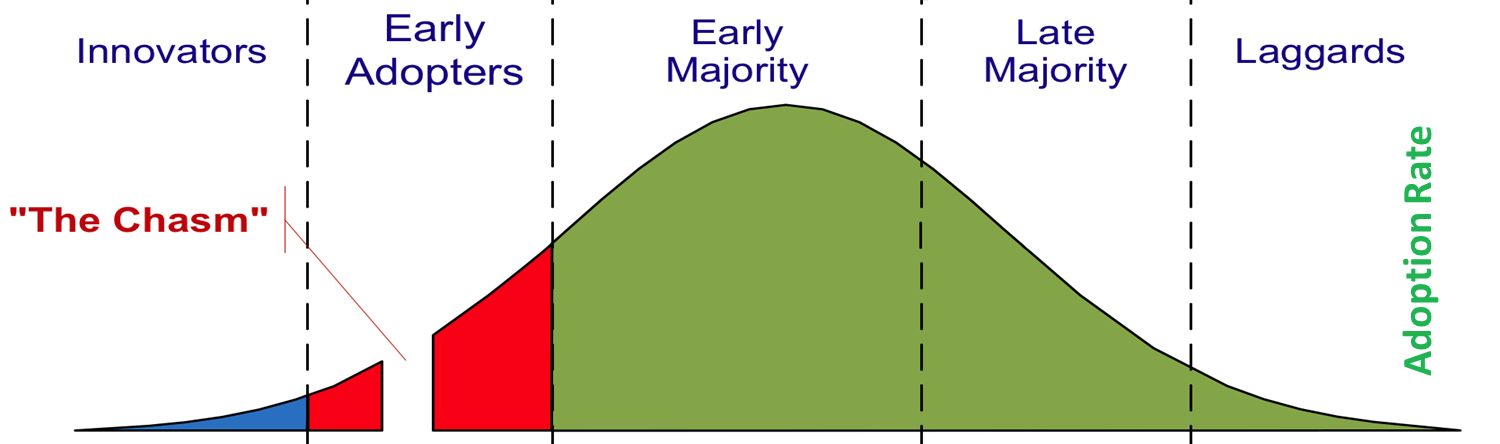

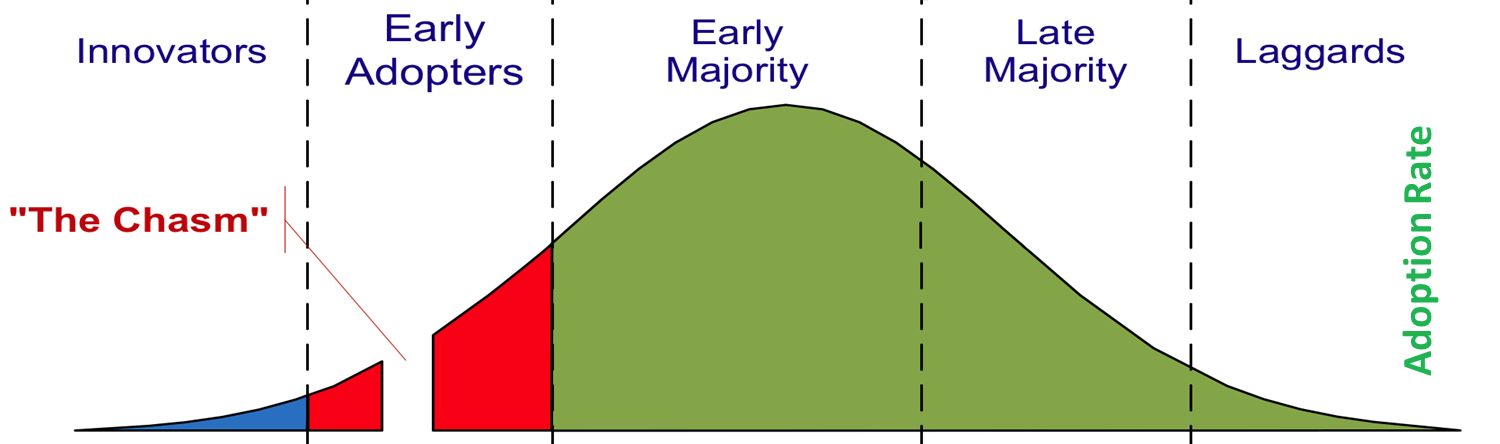

Academia, with its medieval era academic robes and feudal system power structures, is going to be disrupted by technology in ways that will make what has happened up to this point seem inconsequential. While academia has held out longer than some other powerful institutions, it is vulnerable to disruption for the same reasons, and recent trends in higher education have only exacerbated the situation.

Why does disruption occur? In every case, the product or service offered is similar, but the digital alternative to the traditional one has been more convenient and/or less expensive to the customer. When that happens, the transition occurs rapidly. Let's look at some examples. Newspapers used to be big businesses, and they carried great influence and power, but the thing that drove newspapers was advertizing. When Craigslist provided a convenient online alternative to searching the classifieds, newspapers began to lose readership, which started a rapid downward spiral. Apple has been the cause of several industry disruptions. With iTunes, Apple gave music lovers an easy, convenient way to buy music online, and the physical sales of CDs rapidly dwindled. Apple did it again with the iPhone, resulting in the collapse of the previous phone market leaders, Nokia and Blackberry. Amazon disrupted book sales, and later the entire catalog sales industry. Netflix did it for video, and the once ubiquitous Blockbuster video chain ceased to exist within a few short years. Uber seems to be doing it for taxis, and AirBnB for accomodations. Apple has, itself, been disrupted in music by streaming services like Spotify and Pandora. There is no traditional market that is unaffected by digital transformation.

In academia, the first challenges by the forces of disruption, the online and for-profit universities, failed for several reasons. The quality of the education was not very good, and the delivery system was also pretty poor, but the cost was the same, so they produced a bad product that nobody wanted. Defaults on student loans were higher at for-profits, where the degree was of low value, and so funding organizations became more discriminating. Accreditation has also created an OPEC-like cartel but, as with OPEC, all it takes is for a major player to go its own way and the whole thing collapes. Traditional academia has some serious problems too.

Problem 1: For decades, a college degree was what the high school diploma used to be; a ticket to a good job. However, that drove everyone, even the grossly unqualified, to go and get a college degree.

Problem 2: Colleges got greedy. Willing to accept anyone who could pay, and even those who took on enormous student loans for questionable degrees, colleges saturated the market with graduates and the bachelor's degree became devalued. For a while, universities solved that problem by offering Master's degrees, but now that market is flooded too.

Problem 3: Tuition costs keep going up, because of state cuts to higher education, and because highly paid administrators have gone on building sprees to try to make their universities more appealing than those of the competition.

Problem 4: To stem the rising costs, administrators have been gradually phasing out the well paid, highly qualified, tenured professors as they retire, and replacing them with low paid, less qualified instructors on annual contracts. This has had the added effect of solidifying the administrative power base, since tenured faculty were often the most resistant to the demands of administrators to lower standards and keep paying students in the pipeline regardless of their potential.

The modern baccalaureate degree is devalued. It is no longer a ticket to a good job, the quality of the education itself has declined, and the cost remains exorbitantly high. These problems create a situation ripe for disruption.

All that remains is for employers to realize that they cannot effectively distinguish between job applicants based on whether, or from where, they have a bachelor's degree, and to begin prioritizing other selection criteria. When demand for the bachelor's degree dries up, there will be a lot of academic real estate coming onto the market as universities collapse. Why won't universities just tighten their standards and produce higher quality graduates? Those with strong reputations will be able to take that approach, because it's not just a degree, but a Harvard or Yale or Stanford degree. But graduates with degrees from "generic university" will find that their diploma is worthless, and that they are saddled with a huge pile of student loan debt that bought them nothing but a 4-year party. The administrators running Generic U will need to rapidly change their institution's offerings, or see enrollment plummet. Unfortunately, universities are led by cautious, change averse people, and so most of those institutions will keep on doing what they've always done and they will fold before leadership has any idea what happened.

The successful disruptors will be the organizations that figure out how to do two things:

1) Rapidly assess the abilities of students (grading students in the way that eggs, or olive oil, or maple syrup is graded, by quality) and sell those ratings directly to employers. Curiously, the lists employers provide do not generally involve any knowledge of the job itself, but rather are heavy on personality traits and attitude indicators.